Twenty-five of 26 seats in Gujarat go to polls today, May 7. For nearly three decades, the state has seen no other party than the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in power. In 2019, the party had won all 26 seats and this year it opened its account with an unchallenged victory in Surat. Home turf of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, an overwhelming support still goes towards the BJP due to his popularity but it will be interesting to see if the Opposition can cause a dent in this majority this time.

Under 'Gujarat Model' Of Development, Muslim Ghettos Remain Neglected

Muslim ghettos in Ahmedabad are dilapidated and neglected

The vast stretches of the main road of Sarkhej, Ahmedabad, become narrower, the buildings smaller and more congested as you take a detour and enter into what is known as India’s largest urban Muslim ghetto. Surrounded by settlements of the riot-hit minority community, the lanes lead up to a towering brick wall with fencing on top, built with the sole purpose of separating the Muslim population from its neighbouring Hindu colony, Vejalpur. This is Juhapura, an area located just a few kilometres away from the heart of Gujarat’s largest city, Ahmedabad. While it was founded as a rehabilitation project for the flood-hit victims in 1973, the area took a whole new meaning with a series of communal tensions over the next few decades.

The contrast here is stark: tall buildings lining up the Hindu colony, and waterlogged lanes, crumbling small houses and the poor economic conditions in the Muslim settlement. The streets of Juhapura are brimming with autorickshaws and cycles, lined on either side by meat shops, barber shops, mechanics and offices of travel and estate agents. It is usually at its busiest when the sun is up and shining. The bylanes open into multi-storeyed concrete structures stacked up like Lego blocks. Inside, the rooms are small and functional, housing a family of four or more and bearing the weight of an urban life amidst neglect and decay.

Shagufta Anjum, 38, lives on one of these lanes of Juhapura area. Early in the morning, as she prepares to get ready for the day, she calls out to her brother looking up to the corridor outside a cramped nine-by-nine room, “Switch off the pump. There has been no water since yesterday.”

“Today is jumma,” she turns to us and says. “But look, we don’t even have water to bathe. See how much the government is doing for us.”

The summer months are particularly difficult for the poorer residents of the Juhapura area of Ahmedabad, where the government turns a blind eye when it comes to setting up facilities. “The water we get is anyway dirty, and we do not even get it regularly. There are hardly any street lights. The most they (government) have done for us is send the garbage truck once in four days,” she says, laughing as if she was accepting her fate, as if there is no chance their area could witness the ‘Gujarat model’ of development everyone else boasts of.

Juhapura is the epitome of the segregated city that Ahmedabad is—where the lines between the new and the old may get blurred, but when it comes to class, caste, religion and economic activity, the divide is more stark than anywhere else.

Although not the only Muslim ghetto in the city, Juhapura is the epitome of the segregated city that Ahmedabad is—where the lines between the new and the old may get blurred, but when it comes to class, caste, religion and economic activity, the divide is more stark than anywhere else.

Juhapura’s emergence is marked by the city’s decades-old history of communal tensions as Muslim citizens moved out from the densely packed walled city on the eastern side of the Sabarmati River and rehabilitated themselves in the city’s ‘urban’, more affluent western periphery. Initially, it was a few thousand people trying to come out of the deep-rooted Hindu-Muslim divide. But the recurring riots in Ahmedabad in 1969, 1985, 1992 and 2002 further cemented the borders. In the aftermath of the 2002 Gujarat riots, the population here grew manifold as more people were pushed out of Hindu-dominated areas like Khadia and Teen Darwaza. Juhapura became a safe zone for Muslims in Ahmedabad.

But it remains untouched, unseen by the government. It was part of the erstwhile Sarkhej assembly constituency, which used to be Union Home Minister Amit Shah’s bastion, and now falls under the Vejalpur constituency. Shah, who was seen as an undefeatable contestant in the area, was also known for leveraging the communally-torn fabric to appease the Hindu majority. In the Lok Sabha elections, on the other hand, the area falls under the larger Ahmedabad West constituency currently held by the BJP’s Kiritbhai Solanki. The party has fielded Dinesh Makwana from the seat this time.

In the years following the 2002 riots, Gujarat witnessed a rapid infrastructural boom that came to be known as the ‘Gujarat model’. The model was driven by the then Chief Minister Narendra Modi’s neoliberal policies, which were used in the electoral campaign for the 2014 Lok Sabha polls. Modi was projected as a Vikas Purush even as the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) promised to replicate this development on a national level after coming to power. But even within the city, this model of development has not reached everyone yet. To a large extent, the residents of Juhapura rely on their elected corporators of the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC), but even then there is very little progress.

Over the years, the people living in the ghettos of Ahmedabad have worked their way up to build a life on their own terms. “People say big things about the Gujarat model, but a few tall buildings or a riverfront will not help us fill our stomachs—employment will. And there is no employment here. The government has not done anything for us. There is clear discrimination,” says Fareed Qureshi, a resident of Juhapura.

Despite decades of communal segregation, residents of Ahmedabad have oddly remained silent about their demands.

On the face of it, even Juhapura can be mistaken for a ‘developed’ area with its sprawling high-rises, luxurious bungalows along a widened main road. But take a look behind these buildings and you will still find concentrated communal pockets. The scars of historical segregation, it appears, never went away. Areas within Juhapura are deprived of basic government infrastructure and public services on the basis of religion. Residents allege lack of education, transportation, water supply and sewerage. Even with the Lok Sabha elections coming up, there are no promises made for the people living in this area.

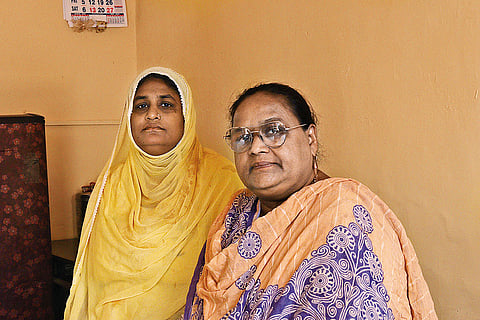

Shagufta’s aunt Fatima, who has lived in the area for the past eight years, says that even sending kids to school is a struggle. “There are no municipal schools in this area because the government does not build anything here. The nearest one is several kilometres away. Every day we have to book an auto or arrange private transport to send the kids to school. It costs Rs 600 a month per auto. The buses don’t enter this gali. Ultima-tely, we end up spending nearly as much as we would have if our kids were going to private schools,” she laments.

Shagufta, her sisters and her family moved to Juhapura from Dariyapur in old Ahmedabad during the last 10-15 years as they could not sustain a life within the dilapidated walls of the old city. “The houses were very small there and nearly falling apart. We had to move out,” she says.

***

The 600-year-old walled city, of which Dariyapur is a part, is on the UNESCO World Heritage List. But more and more buildings are crumbling down because of the negligence of the authorities. The negligence, residents living in the area say, stems from a similar bias seen in other Muslim-dominated parts of the city. The AMC sends a few notices to mark buildings as “dangerous and dilapidated”. But here too, there is rarely any further action or aid from the authorities to prevent it from turning into an accident site.

Tasleem Malik, a beautician living in Sarkhej-Ojha area, visits her parents in Dariyapur every weekend. This is her family home where she grew up and where the family has lived through generations for over 100 years. “This house is very old, but my parents do not want to leave,” she says. Tasleem’s family has seen every phase of the riots in Ahmedabad. They faced curfews, saw people turn against each other, saw bloodshed, though in Dariyapur the atrocities were “not that grim”, according to police records.

“It is Allah’s grace that everyone in my family is safe. The things we saw happening in front of our eyes those few days are unspeakable,” she says, but quickly notes that everything has been fine since then.

Over the years, the people living in the ghettos of Ahmedabad have worked their way up to build a life on their own terms.

When nudged a little more, she says that there are a few scattered Hindu-Muslim incidents, but maintains that these are only minor issues. “Aisa to chalta rehta hai (These things keep happening),” she says.

Mohammad Ikrama, a qari at a Dariyapur mosque, says, “We always welcome people of all religions to our area. But sadly, the same doesn’t happen when we go to a Hindu colony. A few days ago, four Muslim men went to Isanpur (an area on the outskirts of Ahmedabad) to have lassi and were attacked there. They are now hospitalised.”

Ikrama feels that these tensions are created by politicians to further divide the communities on the basis of religion. He recollects the recent “ghuspaithiyan” remark made by Prime Minister Narendra Modi during a rally, and says, “We keep seeing these kinds of remarks made by our leaders. But why must there be this hatred? All we ask for is to live in peace and harmony. Whoever is our representative should ensure brotherhood amongst all communities so that people can work freely, our businesses flourish and there should be no fear within our community.”

Despite decades of communal segregation, residents of Ahmedabad have oddly remained silent about their demands. The minority communities have now started taking matters into their own hands, supported by their local committees and religious trusts, because they feel they will never get any support from the government.

When asked about why there is such a silence about this pertinent issue, V Divakar, curator of Conflictorium, a museum in the heart of the walled city, says, “The idea that riots do not happen anymore in Gujarat is a false narrative. Although it may not be as violent or large-scale, there are smaller incidents happening everywhere. The right-wing has promoted the Gujarat model as something extraordinary, but such infrastructural growth happens everywhere. What is interesting here is how there have been no social movements, no opposition. The opposition has been completely terminated.”

He goes on to say that the ‘Gujarat model’ is “just an eyewash”. “You talk about development and business to take away social responsibility. There are no concerns for labour; people are being hired for as little as Rs 50 a day,” he says.

Ahead of the Lok Sabha elections, the saffron-laced electoral landscape of Gujarat has once again become evident, where voting has, for years, been dominated by the aura of only one leader—Narendra Modi. But in the shadows, an opposition voice is simmering. Even among the Hindu communities, where people praise the roads, buildings and schools, they are unhappy about inflation and rising unemployment.

There is a disconnect in Gujarati society between social and economic growth. On the economic front, Gujarat has, for years, remained above the national average, powered by the dominant business fraternity. However, on social indicators, it has underperformed.

For a majority of the population, the vote may still favour the party that has ruled Gujarat for the past 25 years, but there is a strange hunch, a constant buzz that this may be the last democratic election in India. Perhaps, the quietness in Gujarat about election campaigns, just a week away from the polling date, signals a reality many still refuse to see.

Sharmita Kar in Ahmedabad

(This appeared in the print as 'Under The Model Town')