“Everyone’s a murderer. You just have to meet the right person,” says the character of Jefferson Grieff in the Netflix show Inside Man. Grieff, played by Stanley Tucci, says this in the context of his white collar appearance. He is a studious, respectable-looking man. He doesn’t look like a murderer. But rage, building quietly over time, or which explodes in a single moment of madness, can lead the most unlikely person to take another person’s life. We know this.

Crimes For Sport: Why Do Athletes Throw It All Away In A Moment Of Madness?

Sportspersons have a long and gory history of murderous misdemeanour. We look at some of the cases

Yet, when it happens, we are surprised. “He/she did not seem the type,” we say. There is no type.

The world of sport reminded us of this on Valentine’s Day, 2013. A white athlete with choirboy looks, a sprinter revered around the world for competing in the able-bodied section of the 2012 Olympics with prosthetics for legs, a man who could have ended up with head of state status post-career - picked up a gun in a dark apartment in Pretoria while his girlfriend cowered in fear in the bathroom.

Oscar Pistorius had a temper. The world didn’t know it. His girlfriend, the model Reeva Steenkamp, did. So did his ex, Samantha Taylor.

Pistorius was born without a fibula bone in either of his legs. To give him some chance of mobility in his life, both his legs were amputated when he was about one. His mother Sheila did not want him to turn into a self-pitying sort. She pushed him into sports.

Pistorius became one of the biggest, odds-defying stories in sports history, running like the wind on carbon-fibre blades. ‘Blade Runner’, they called him. He not just dominated the Paralympics, but also competed in the able-bodied competition in the 2012 London Games.

On that unfortunate Valentine’s Day in Pretoria, Pistorius, then 27, shot four bullets through the bathroom door of his apartment, killing Steenkamp, older by about a year. Pistorius’ mother often slept with a gun under her pillow owing to the high crime rate in South Africa. Pistorius too was known to be paranoid about break-ins.

He was also fond of guns. In an essay titled ‘Bantu in the Bathroom’ (the headline draws from an essay/book on race and sexuality and how these de-stabilise us, by Eusebius McKaiser, a South African political and social theorist and radio talk-show host. entitled A Bantu in My Bathroom:Debating Race, Sexuality and Other Uncomfortable South African Topics), feminist theorist, Jacqueline Rose, closely examines the various forces at play in the Pistorius case, including racism and ideas of masculinity. Rose writes that between Pistorius, his father, two of his uncles and his grandfather, his family owned 55 guns. At the time of his killing of Steenkamp, Pistorius was expecting six more firearms, including a semi-automatic of the kind used by the South African Police Service, and 580 rounds of ammunition. The essay also reveals that the bullets that killed Steenkamp were the kind that expanded after penetrating a body.

Pistorius’ defence was that he thought Steenkamp was in bed and the person in the bathroom was an intruder. But there were gaping holes in it. While he initially received a relatively lenient conviction for culpable homicide and not murder, he was eventually ruled guilty of murder and jailed for 13 years. The investigation revealed the subtleties of Pistorius’ personality, and his relationship with Steenkamp. Some of their text messages, which were read out in court, hinted at a romance in which affection -? calling each other Boo or Baba – coexisted with jealousy and insecurity.

One of the messages, from Steenkamp to Pistorius, was, “I’m scared of u sometimes and how u snap at me and how u will react to me.” In another message, from Pistorius to Steenkamp, which was not a response to the message above, he said, “I am sorry for the things I say without thinking and for taking offense to some of your actions. The fact that I’m tired and sick isn’t an excuse. I was upset that you just left me after we got food to go talk to a guy and I was standing right behind you watching you touch his arm and ignore me.”

Pistorius’ ex-girlfriend, Taylor, also testified at the trial. It gave further clues into Pistorius’ nature. Taylor said he had a short fuse, and he would scream at her and even her family members. She also said he cheated on her, including with Steenkamp, and that he had drawn his gun out of anger at least on two occasions in her presence. Once, it was because a policeman had stopped his car and touched the gun.

It’s almost a decade since the ghastly events of February 14, 2013. The latest is that Pistorius is angling for parole and an early exit from prison. In June 2022, he met Steenkamp’s father, Barry, as part of a rehabilitation process. It was a difficult meeting, tense and emotional. A tearful Pistorius asked to shake his hand. Steenkamp Sr accepted, but did not explicitly forgive him.

“I asked him certain questions…and I expected different answers. He gave me his truth, but I didn’t get my truth,” Barry Steenkamp said in the documentary My Name is Reeva. “He came in, he went on his knees and he took my hand and shook it. He thanked me and [told me] how sorry he was and how he can’t stop thinking about that moment [Reeva’s death].

“It was a touching moment. I could’ve said no and left it but we did shake hands. I didn’t say ‘I forgive you,’ I just said ‘Thank you’”.

Steenkamp’s mother, June, did not go for the meeting. “You’ve stolen her life,” she wrote in a letter to him. She does not believe Pistorius has been entirely honest and unless he did that, she says he won’t find forgiveness.

Rose, in a brilliant contextual analysis of the case through the prisms of the history of South Africa, apartheid, masculinity and bathrooms, comes to the conclusion that “we should not disavow our hatreds in a futile effort to make ourselves – to make the world – clean.”

Cleaning the world of someone he was responding violently to was also the strongest desire in the saga of Syed Modi. The 26-year-old Indian badminton champ, known to be one of the most humble and non-threatening of men, was shot dead after practice on July 28, 1988,? at KD Singh Babu Stadium in Lucknow.

Who would want to kill a boy who was accomplished – one of the few Indians to beat Prakash Padukone, and a winner of the Commonwealth Games gold and eight national titles – and unlikely to have any enemies?

But Lucknow and sports insiders had known that his marriage to fellow player Ameeta Kulkarni was in an unimaginable mess, and for no fault of his. Kulkarni was brazenly involved with Sanjay Singh, the married politician related to former Indian Prime Minister, VP Singh. Modi even suspected that the daughter born to Kulkarni after their marriage was not his.

Despite everything, Modi was ready to forgive her as long as she ended her relationship with Singh. But Kulkarni and Singh continued their liaison. Modi became a hindrance to the illicit couple. It was alleged that Singh got him eliminated with the help of Akhilesh Singh, a leader with a criminal record, and two hitmen named Jitendra Singh (Tinku) and Bhagwati Singh (Pappu).

According to a September 1990 media report of the trial, SG Sawant, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) lawyer, alleged in court that Sanjay Singh met Akhilesh Singh in Yatrik Hotel in Allahabad on June 18, 1988, to plot the hit on Modi. About a month later, Akhilesh Singh introduced Bhagwati Singh to Sanjay Singh. The next day, Bhagwati allegedly received Rs 50,000 from Sanjay Singh to carry out the murder.

As it happened, Singh and Kulkarni were acquitted of murder charges. Singh then divorced his wife, Garima, and married Kulkarni. They led lives of privilege and power.

How could Kulkarni, a player of note, not know better? In her early to mid-20s when the drama played out, was she too young to know better, and too ill-advised. Based on her letters, it appears Kulkarni was torn between feelings for her husband and passion for her boyfriend, and the lure of a privileged life with him.

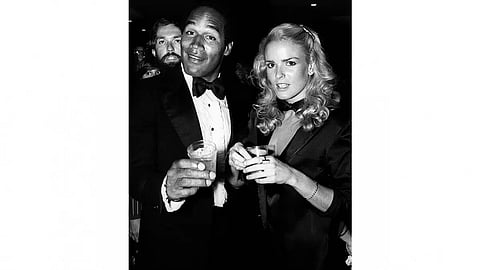

It’s nearly three decades since the OJ Simpson episode, but it remains, arguably, the most famous sports crime case. An accomplished and charismatic football player, although one with a violent temper, Simpson allegedly murdered his ex-wife, Nicole Brown, and her male friend, Ronald Chapman, in Los Angeles and was chased by cops as he attempted to flee as a passenger in a white Ford Bronco. The media attention the case received, and the shocking acquittal of Simpson, further added to its impact on the public.

Simpson and Brown had a tempestuous relationship. There was at least one occasion where he beat her so badly she had to be hospitalised. But Brown and her family were financially dependent on Simpson. Besides, the couple had two children. They tried to make it work till it became clear that divorce was wiser.

The thought of Brown with another man, however, remained unpalatable to Simpson. Even after the divorce, he intimidated and controlled her. The trigger for the murders, reportedly, was Brown’s friendship with Chapman. On the night of June 12, 1994, he allegedly stabbed the two to their deaths at Brown’s home.

Beyond domestic violence and jealousy, Simpson’s own emptiness and frustration at his post-career life contributed to his spiralling. Crime writer, James Ellroy, remarked about Simpson’s scandals and serial philandering, “Second-rate acclaim and the pursuit of empty pleasures wear a guy out.”

As far as the verdict goes, there was obviously a race angle to it. The Simpson case took place just a couple of years after the Los Angeles riots of 1992, which were precipitated by the acquittal of white police officers in the beating of an unarmed black man named Rodney King. Simpson had always been a reluctant black hero. He lived in a predominantly white neighborhood and left his black wife to marry Nicole, who was white. And yet what helped him during his trial was the support of the black community. Johnnie Cochran, a lawyer on the infamous Simpson defence team, was black too, and some reckon that Cochran used the public mood expertly in his arguments for getting his client off the hook.

Indian wrestler, Sushil Kumar, is another high profile and bizarre name in sports crime. The double Olympic medallist is currently in jail on the charge of beating a young wrestler named Sagar Dhankad to death in May 2021 after a property dispute and his rising resentment

towards Dhankad.

Beyond that, Kumar’s case is about the hierarchies and internecine tussles in Indian wrestling. For athletes in strength sports such as wrestling and boxing, it is not uncommon to turn to a life of crime. For years they have worked as muscle for gangsters, builders and politicians, all work that goes under the name of ‘Finance’ in Haryana. In the process, they become quasi-gangsters themselves. Kumar, by virtue of his feats, and being the son-in-law of former wrestling great, Satpal Singh, was the intimidating lord of Chhatrasal Stadium, the nerve centre of Indian wrestling, developed by his father-in-law.

So much so that at the 2017 National Championships, when Kumar returned to competitive wrestling after a three-year break, his quarterfinal, semifinal and final opponents all gave him a walkover, that too after touching his feet. It was reminiscent of Idi Amin’s boxing opponents deliberately losing to him, as victory would mean death or severe punishment.

But bullying is often a symptom of insecurity. Kumar, according to a Delhi police chargesheet, was feeling threatened by Dhankad. He feared that some of his own trainees and coterie members were passing information about him to Dhankad and his friend Sonu. The chargesheet also says “He (Kumar) started planning to strike them hard to teach them a lesson and re-establish his supremacy,” and “When he realised that some of his own students/trainees were passing information about him to Sonu and Dhankad, he felt betrayed and developed deep grudge against Sonu and Sagar for loss of respect in the eyes of his students and further betrayal by them by passing his information”.

What compounded matters was that Dhankad lived in a flat owned by Sushil in Model Town, Delhi. The two had been quarrelling over the rent and Sushil wanted Dhankad to vacate the flat. The hellbroth of vitriol in his brain led Kumar and his bunch to corner Dhankad and four other wrestlers in Chhatrasal Stadium and rain blows on them.

Another Indian sports headliner currently in prison is Navjot Singh Sidhu. For all his humour and oratory powers, Sidhu has always shown a tendency to fly off the handle. And that is what happened in a Patiala parking lot on December 27, 1988. Sidhu and his friend Rupinder Sandhu got into a skirmish over right of way with a 65-year-old man named Gurnam Singh who was on his way to the bank. Sidhu had blocked the road at Sheranwala Gate Crossing in Patiala and Singh asked him to let him pass. it escalated into a fight. Sidhu and Sandhu proceeded to beat up Gurnam Singh and Sidhu then fled the scene. Singh later died of his injuries in hospital. In 2018, the Supreme Court convicted Sidhu under Section 323 for “causing hurt”, even though it acquitted him of culpable homicide (Section 304). The sixer-smashing, shayari-spouting, laughter challenge taali thoko-ing Navjot Singh Sidhu had a foul temper and had hit a much older man. In 2022, he was sentenced to one year of rigorous imprisonment. Now he is serving the sentence in Patiala jail.

Rose, speaking of Pistorius, writes, “In his testimony, Pistorius repeatedly insisted that he wasn’t thinking when he fired four shots through the door: ‘That split moment I believed somebody was coming out to attack me. That is what made me fire. Out of fear. I did not have time to think.’”

This split moment is what makes a man do the unspeakable, which is to kill. The impulse is in us all and we have to tame this unthinking

moment within.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Crimes for Sport")