Against the visuals of water ripples, a lovelorn heart types ‘Desire’s d surprise f your skin ... (with an evil emoji)’. Almost a decade old, Tanushree Das’s directorial For You and Me unveils the desires and passion experienced by a couple in a modern, long-distance relationship. There are no dialogues and no actors, yet the short film delivers what it aims to, leaving its audience aching for their loved ones.

Dreamscape: Love Is Overrated For You And Me

There are no actors or dialogues. Simply through the metaphors of texts and images, Tanushree Das manages to leave the audience aching for loved ones in her short film 'For You and Me'

‘Ev’ry time we say goodbye’ plays in Ella Fitzgerald’s captivating voice in the beginning, tearing apart a lover’s heart away from their beloved. ‘Ev’ry time we say goodbye, I die a little. Ev’ry time we say goodbye, I wonder why a little.’ The song of separation in the backdrop of an Asian landscape traverses to the pain in Farida Khanum’s Aaj jaane ki zidd na karo.

A part of Sudarshan Shetty’s Who is Asleep Who is Awake curation for the 2022 edition of the Serendipity Arts Festival, For You and Me attempts to use lens-based media to capture and contain reality of imaginations. Through the metaphors of texts and images, the film breaks down desires, imagination, distances, worlds, and dreams. Exerting the liberties of cinematic representation, the film defies the stable, structured idea of evoking emotions through people and rather chooses to connect to its audiences through objects of reminder, reminiscing, and longing.

As we often transcend from physical realities and wander off beyond the tangible materialities, the unseen protagonists in the film break beyond the boundaries that separate them by time and distance, towards the soul united by passion and expression. ‘I can see you reading. I can feel/touch you’, they whisper to each other through the medium of messages. The film traces a couple’s journey in a tech-savvy, postmodernist world that is not dictated by the logic and reasons of establishments. “One does not necessarily have to be in a state of coma to be lost from the physical structures around them,” Das says.

The film is both silencing and loud in bits and pieces, like the fragments of one’s soul and body. Das’ idea of filmmaking as a meditative practice is reflected in its visuals and audio. For You and Me takes up the task to evoke emotions in its audience in the absence of actors or faces, which Das defines as what we associate primal sentiments to.

The film relies on the brilliance of its director, cinematographer and sound and tech team to capture the essence of what objects represent. It’s not necessary that we miss someone in an unadulterated way. “Sometimes even as we see our pets curled up on the same couch they last sit on before leaving, we reminisce, apparently just as our pet,” she says.

For Das, the movie is closest to her heart as multiple texts used for the project were texts exchanged between her and her partner when physical distance separated the two. She says that the idea behind a constant transition from urban to semi-urban spaces in the film’s visuals is to find the connection for you and me, move beyond personal, and expose the vulnerabilities of longing and passion. In the constant work-play that we are a part of, we also incessantly try to find a connection and meaning to the world. And this meaning, as Das puts it, cannot be one absolute meaning, but they are floating ideas through which people connect.

She believes that this film’s cinematography replaces the traditional chronology of imposition of one’s own ideas into places, time and space, and rather captures the landscapes and scenes in all its naturality. “Each place has its own language, its own visual,” she adds.

‘Love is overrated’, Das quotes as she begins to say that it is the pining for one’s physical presence, needfulness and longing that defines a relationship. “You often remember your sweethearts from the fights you have had and challenges you passed through, together,” she says.

She uses a beautiful analogy to define the differentiated approaches for love and relationship, when together and when apart. “One often asks their partners to take a shower and complain about their odour. However, we cherish the person for months in their shirts and clothes when apart, sniffing them,” she says.

The dissonant background scores with horns blaring, alarm ringing, pressed doorbells, and typing sound awakens the audience time and again from the soothing whispers of shower, silence, tunes, air, and rain. The makers use Spike Milligan’s idea of telling you, ‘I cannot tell you in words ...I can only tell u in trees, mountains, oceans, and streams.’ The beauty of defining one through the objects of nature breaks the binaries and boundaries established by verbal language and exposes one’s flowing thoughts in all their vulnerabilities. It is in the backdrop of these exchanges; rains make repeated guest appearances on the screen.

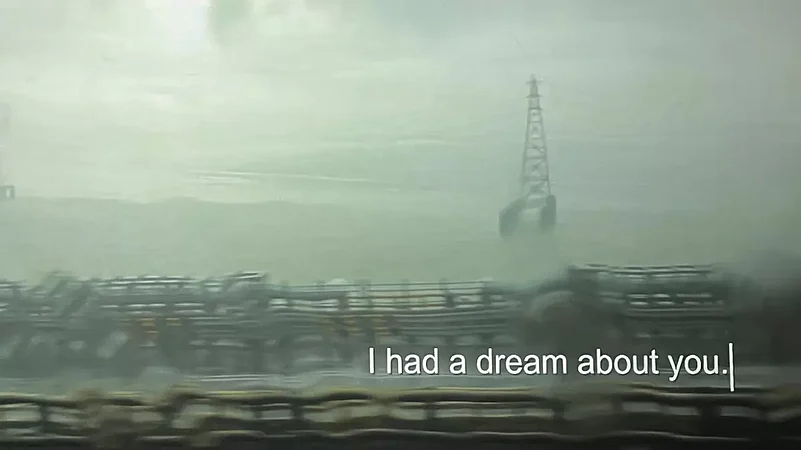

Quenching the midday thirst of lonely tarred roads, rain blurs the rear windshield of a car in motion as the shadow of a woman struggles with gripping loneliness, moving away from what her heart craves, and her body longs for.

However, For You and Me works within the heteronormative structures of a monogamous relationship, alienating queer longingness and the idea of platonic love. It only focuses on the physical separation by choice or circumstances and pines for physical reassurances. The film while romanticising the idea of a long-distance relationship also does not take into account the frustration and exhaustion that goes into keeping long distances alive. There is no mention of the energy that one is often drained of, in a relationship where there are no reassuring hugs from your partner at the end of the day.

There is, however, the mention of pain as a text reads, ‘I don’t feel fear, I feel pain’ as the visual of a floating cloud weaves the viewer’s imagination which soon shifts to a shower, of flowing emotions and pain. Das also shares that the film was initially perceived by her and her partner as a personal project, drawn from their own separation, never meant for the outside world. But in the process of ideation and brainstorming, they realised the universality of their long-distance relationship that can sufficiently be defined through their exchange of texts. “We never wrote down the film, it was conceived,” Das explains.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Dreamscape")

- Previous Story

Joker: Folie à Deux Review: Joaquin Phoenix and Lady Gaga Can’t Rescue a Flubbed-Experiment Sequel

Joker: Folie à Deux Review: Joaquin Phoenix and Lady Gaga Can’t Rescue a Flubbed-Experiment Sequel - Next Story