Anyone who was in any kind of relationship with Hanuman, however tenuous, has a story about his grace. I do, too. Thi-rty-some years ago, when I was writing my Master’s thesis at a US university, I desperately needed a copy of the Hanuman Chalisa. As I was walking glumly along one evening, I found myself in step with an older Indian couple. We started to chat. In an uncharacteristic burst of candour, I said that I was looking for a copy of the Chalisa. The lady stopped and pulled a copy out of her bag. “I always carry this, but today is Hanuman’s day and I think he wants me to give it you!” I still have that well-thumbed copy. Obviously.

Behold The Mighty Forty

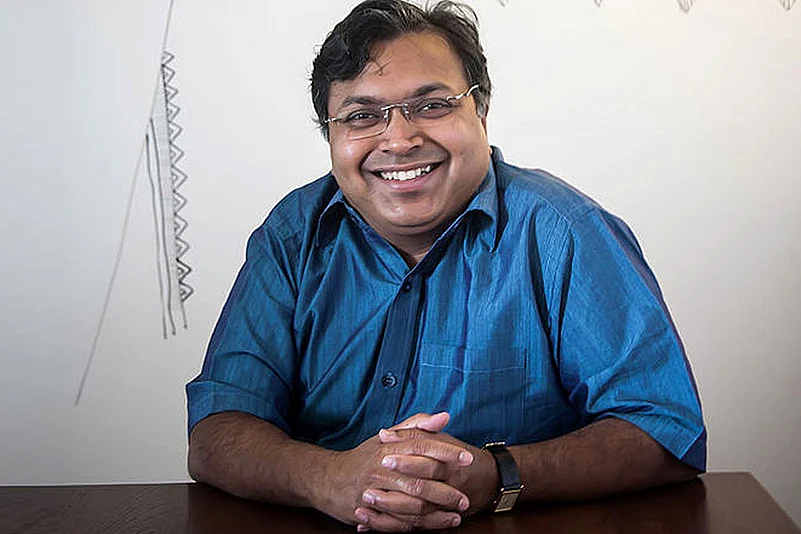

Pattanaik takes each verse of the Hanuman Chalisa, unpacks it, then brilliantly links it to other stories and ideas across the vast sea of Hinduism

It is this beloved text, imbued with magical powers and wish-granting properties, that Devdutt Pattanaik bri-ngs to life in My Hanuman Chalisa. The 16th century text is attributed to the poet Tulsidas, composer of the hugely influential Ramcharitmanas and a devotee of Hanuman. The Manas and the Chalisa both occupy a central place in north Indian bhakti. Simply the fact that they are referred to by shortened names, endearments, almost, suggests the kind of intimacy with which they are reg-arded. Both are written in Awadhi and use simple metres (typically, the doha and the chaupai) which are easily rec-ited and easily remembered. In this bhakti schema (one of many in north India and one among even more in bhakti traditions across the sub-continent), Hanuman is the ideal devotee—loyal, selfless, tireless, unwavering in trust and faith— a model, in fact, for how a human should be devoted to Ram. In Tulsi’s recorded hagiographic life, Han-u-man is the gateway to the poet’s bel-oved god (the poet encountered the supra-natural monkey-god on more than one occasion) and the Chalisa ref-lects that theological paradigm of clo-se-ness as well as salvation.

As one would imagine from its name, the Hanuman Chalisa is a collection of ‘forty’ (the text actually has forty-three) verses dedicated to Hanuman. These recount his epithets, extol his many virtues, recall his many extraordinary feats, praise his devotion and ultimately, promise the votary of the Chalisa that his/her every wish will be fulfilled. More than this, the Chalisa’s promise is that approaching Hanuman with love and devotion will take the believer closer to Ram. Hanuman will show the way, will destroy obstacles, will smooth the path to the god that one loves, that is one’s ultimate goal. It is a sweet text, one of aspiration, that simultaneously reminds the reader of her/his own creatureliness and holds out the possibility of transcending it.

This is not Pattanaik’s first book with Aleph—they have his My Gita and Business Sutra as well. But in My Hanuman Chalisa, Pattanaik is at his very best. The book is strewn with his own charming line drawings of Hanu-man, as Pattanaik takes each verse of the Chalisa and unpacks it, literally, metaphorically and mythologically. The original verse appears in English transliteration, then in a literal translation. After that, Pattanaik uses his considerable imagination and vast resources of information to link the verse and Hanuman to other stories and other ideas across the vast and varied landscape of classical and contemporary Hinduism. I would argue with Pat-tanaik’s emphatic statement that Han-uman embodies Vedic wisdom—from what I know, there is a grand and enormously enriching rupture between Vedism and what we now call Hinduism. But, I am sure that were I to make more of this contention, Pattanaik would make a fast and furious argument for how there is, in fact, a continuity bet-ween the two. And I would be (temporarily) persuaded.

I believe that Pattanaik has found the pulse of how Hinduism wants to be und-erstood in the 21st century—with his unique intelligence, he is able to speak both to the liberal mind within the fold of the religion as well as to the illiberal one that stands as its gatekeeper. In this present case, Pattanaik replicates the intimacy with which the traditional Chalisa is regarded by calling his book ‘MY Chalisa’—this is how he sees it, what he understands it as, what he gains from it. At a time when every utterance about Hinduism is contested, we can only hope that such an unequivocal statement of personal attachment to and res-pect for a Hindu text should keep the newly empowered keepers of the faith at bay. As for myself, I shall recite my Chalisa anew, in the hope that Hanuman (and Pattanaik) will eliminate the obstacles that keep so many of us away from Ram. And Hinduism.