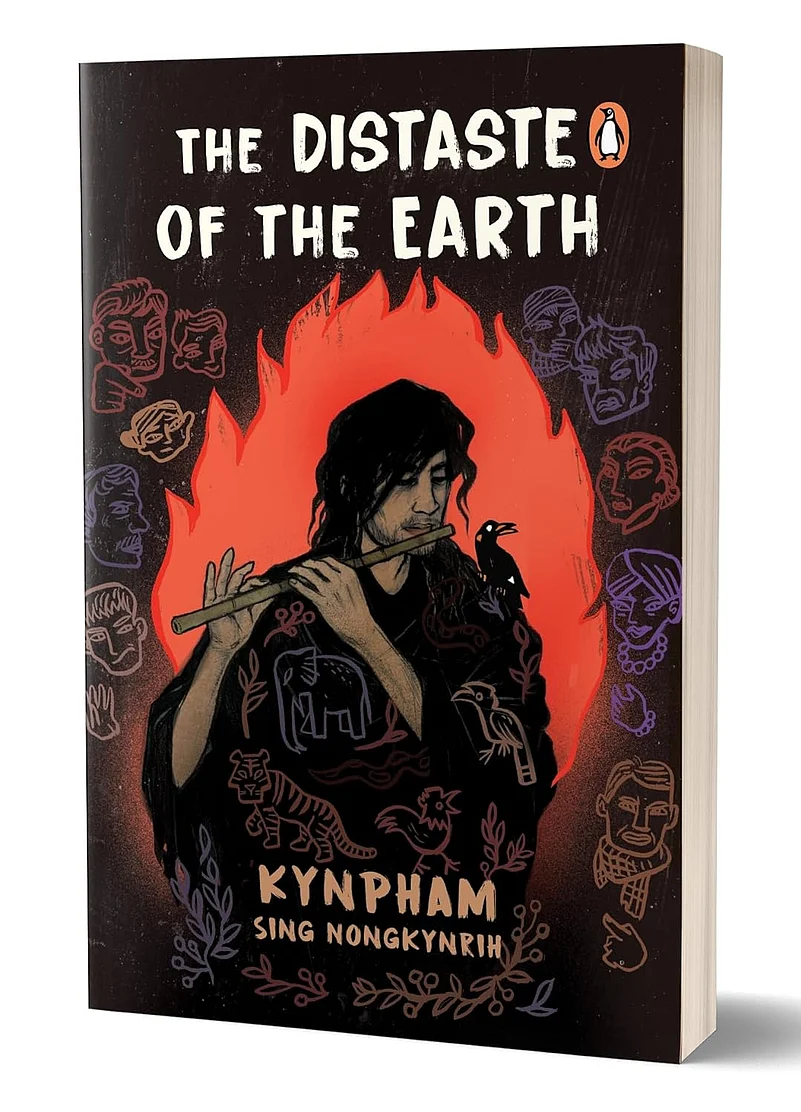

The Distaste of the Earth by Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih

Omens Of Tragedy: A Review Of 'The Distaste Of The Earth' By Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih

Sing Nongkynrih’s story has many layers and explores the realm of gods and kings and their respective powers over the world

Penguin Random House

Rs 799

Tristram running mad through the forests of Brittany deprived of his beloved Yseult, talking to the birds and being protected by the wild. There is a trace of that in this Khasi story of Manik and his flute, Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih bases his tale on what was the true romance of Manik Raitong and Lieng Makaw, like Tristram and Iseult another affair outside the bonds of marriage between a noble from one of the Khasi clans and the new beautiful wife of a king. However, before coming to grips with his story the author starts his tale in a local bar, a pata peopled by drunks and run by a beautiful woman who has had ten husbands despite being in his mid twenties.

Sing Nongkynrih spends a lot of time describing Khasi dress and customs and the traditions of a matrilinear society. There are ornate jainsems or outer garments, dhotis and all the trappings of society. Gradually from the exterior shape of things the drift of the novel becomes more internal, moving first to the relationships between men and women and the reasons for marriage and divorce in a pata. Manik flits on the outskirts of this initial narrative, a madman with a soot smeared face and flute, mocked by the children.

The story spans battles, broken hearts and the reason why people turn to drink before going to the marriage of the new young king. Omens taken by the priests indicate something amiss in the stars but nothing is as it seems.

Sing Nongkynrih’s story has many layers and explores the realm of gods and kings and their respective powers over the world. People disagree over what these powers are and when Manik finally comes into the story in his own right, his first visit to a place outside his village ends in a covid style tragedy for him. Fate throws people into strange situations over which they have no control. A lonely queen loses her heart to the strains of a flute by moonlight and the omens in his marriage are fulfilled.

Sing Nongkynrih throws in fantasy with the animals and birds siding with Manik who is lost in the jungles before he finally returns to the world of human civilisation. There he discovers that his lands and property have been taken from him by the old king and at the same time, he confesses to having fathered the young queen’s child for which the sentence is death. The king’s ego goes against Manik because human rage is greater than justice and the gods are silent on this issue.

Sing Nongkynrih sets the final scenes with pomp, splendour and poetry piling detail on detail heightening the fact that what is happening is against the dictates of nature and the way of the earth. A tale of tragedy comes full circle returning to the pata and the every day with all the beautiful women – for in this book they are all beautiful, in tears.

Is this a fantasy or does it come into the realm of Khasis traditional mythology – most probably the latter. Readers will have to unravel the strands of narrative to reach their own conclusion.