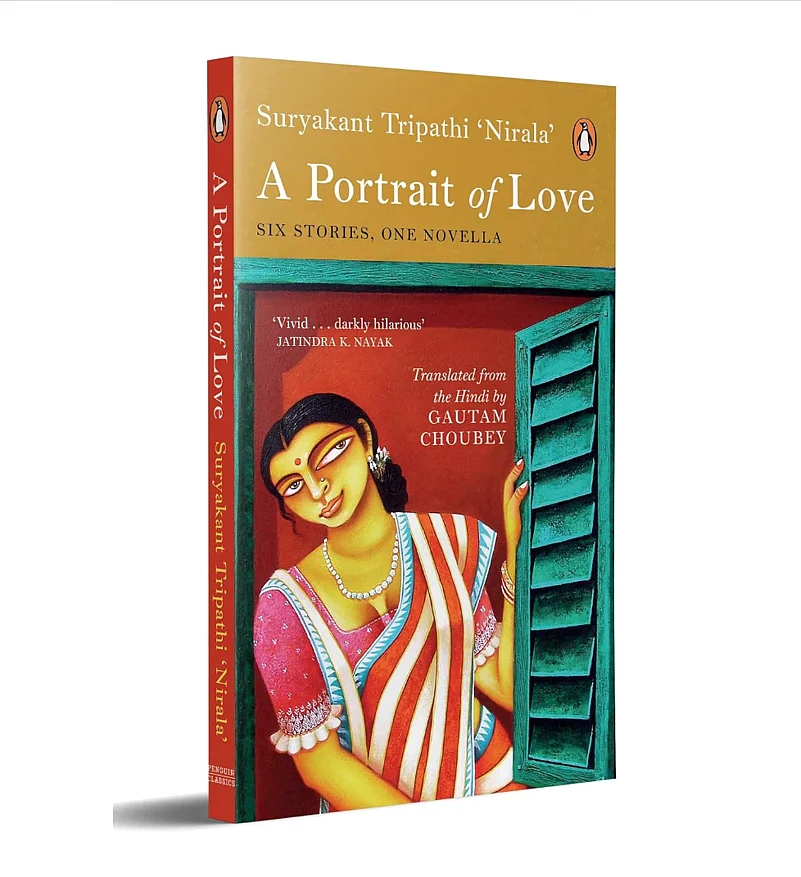

A Portrait of Love: Six Stories, One Novella

Review Essay: A Flag For The Future

In the six stories contained in this collection, the book introduces readers of English to a body of work that will stretch the idea of Indian Writing in English in terms of theme, language and style, by extraordinary degrees

Short Fiction

Suryakant Tripathi ‘Nirala’/ Translated from the Hindi by Gautam Choubey

Penguin Random House India, 2024

Pp. 222 | INR 399/-

To read Suryakant Tripathi ‘Nirala’ in English is a thrill, especially when it makes its appearance via the refined acumen of a sensitive translator. The translative performance is, in many ways, akin to that of letting the horse of the English language run wild over a wide domain of compound cultural truth that is essentially rural and quintessentially Indian. In the case of Gautam Choubey’s recent translation of short fiction by the author in A Portrait of Love: Six Stories, One Novella, one can reasonably assert that this horse of language conquers Nirala’s formidable literary territory with elan.

Acclaimed, largely, for his poems and for his pioneering role in the Chhayavaad movement in the first half of the twentieth century, Nirala transformed the world of Hindi letters with the deftness, intensity and vision of his work in poetry, fiction, and criticism. His voice is unlike any to be found in the repertoire of Indian English writing today for he embodies access to an experience that is as variegated as it is fertile and as tragic as it is rare. A self-taught polygot, Nirala easily bore command over five different languages – Hindi, Sanskrit, English, Bengali, and his own native Bainswari dialect. The epistemology of each of these language-cultures finds place in his work. Very few writers, indeed, can summon Nirala’s mastery over language or equal his astounding range of ideas.

In the six stories contained in this collection – ‘Sukul’s Wife’, ‘Jyotirmayee’, ‘Portrait of a Lady-Love’, ‘What I Saw’, ‘Chaturi Chamar’, and ‘Devi’, and one novella - ‘Billesur Bakriha’, the book introduces readers of English to a body of work that will stretch the idea of Indian Writing in English in terms of theme, language and style, by extraordinary degrees. Here is a thorough master supremely conscious of his mastery -- his precision, sarcasm, thrusts and jibes. Every twist of plot and turn of phrase in these stories is marked by a scintillating self-confidence that while making the telling robust and memorable, also insists vehemently on throwing light on the charm and powerful persona of the storyteller himself.

As Choubey points out in his insightful and well-researched ‘Introduction’ to the book, Nirala is a part of all he writes and it is possible to attempt his “intellectual biography by just following his writings and the order of their appearance.” The capacity, however, of leaving oneself behind in and through the stories one writes so that each story adds to the larger idea of the self, is rare. What is remarkable, also, is the consistency with which all these authorial selves found in his wide works, cohere. There is no conflict or contradiction between the writing self that appears in one story and another. In each is to be found the same detached, contemplative social observer calibrated towards noting the dark passages between appearance and reality– hardened, stoic, tough to please, and impossible to win over except through honesty.

In fact, virtuoso though he was, honesty is that one trait in Nirala that easily outshines his other characteristics and helps to make sense of the rest. Unflinching honesty is the defining factor of Nirala’s manhood, personhood, his conscience as a writer, and that of the protagonists of these seven powerful stories. The title, ‘A Portrait of Love’, in this context, is aptly chosen since what glues each of these stories to their places and to each other is the fathomless love that Nirala has for humanity -- a love that allows him to be both witness and legislator, deeply sentimental and ruthlessly sarcastic, helpless and potent, victim and victor.

As these stories demonstrate, it is characteristic of Nirala to be light-hearted at all times, to not let his burdens crush his spirit, and to consistently wield language as weapon, both against the world and against himself. There is a constant play in several of these stories between ‘seeing’ and ‘being seen’, a transformation of the ‘other’ into self and vice-versa. His language sparkles even when it strikes, disarms even as it condemns, and impresses even in its arrogance. He always has his wits firmly about him. His mind is at repose in its brilliance and his humour is never offensive though it never fails to be incisive. All of this leads to a raciness in Nirala’s style that Choubey artfully captures in his translations, arriving at a near communion with the spirit of his work in an attempt to inhabit his dynamic creative self.

To read Nirala without smiling to oneself all the while would be, mostly, impossible. His humour, however, is not for the uninitiated. Though unpretentious, it is essentially scholarly for it comes from a staggering domain of cultural and linguistic registers. But none of his chosen epistemologies ever fails to intersect with his acute concern for social health. In all that he writes, Nirala’s primary obsession is with this flaming cauldron of society whose rigid and orthodox structures are steadily directed towards keeping large groups of people in check – women, the lower castes, the poor and the illiterate. In ‘Devi’, for instance, he writes: …acclaim doesn’t come without eminence. One can’t become distinguished as a rajrshi, a royal sage, without first being a raja; or legendary as a brahmarshi without first being a Brahmin. No one has heard of a vaisyarshi or a shudrarshi – neither in history books nor in scriptures. […] The point is, eminence by birth is a prerequisite for a respectable life.

Through his fiction, Nirala aims at upsetting this balance to some extent, bravely and with a flourish. In each of the stories in this collection, there is a battle being won by the disempowered or the dispossessed. The victory may not always be physical or may not count for much on the material plane but on the psychological, aesthetic, and moral planes, these victories are inordinately precious. Nirala, as Choubey points out, “launched a blistering critique of all things sacrosanct. However, instead of offering a bird’s-eye view of the socio-cultural landscapes, he studied the local, tracing patterns of percolation, localisation and (mis)appropriations. Consequently, his politics, too, became deeply personal.” In ‘Devi’, the very idea of placing of a beggar woman at the centre of his narrative with the title ‘Devi’ (goddess) is a literary, aesthetic and political protest deeply tied to his personal idea of empathy and social (local) welfare. This story, unlike the others with comforting endings, hints at the sad and imminent death of the protagonist but not without securing an immortal place for her in literature and in the readers’ consciousness.

Irony works deftly in the first two stories of the book, indicating the potential to destabilise a structure that had seemed invincible. In ‘Sukul’s Wife’, irony comes from the fact of his friend Sukul who belonged to “the tribe of boys who were ready to lose their heads but never their choti – the tuft of hair that epitomised their exalted caste” falling in love with and marrying a Muslim woman. In ‘Jyotirmayee’, Vijay who, despite being an MA in English, is “not comfortable with the idea of widow remarriage” and believes “there is a difference between an unwed woman and a widow” (even though the widow in question is a girl who had been widowed at twelve without ever knowing her husband or living with his family), finds himself wedded in a typical arranged marriage to the same woman he had shunned for being a widow.

In ‘Portrait of a Lady-Love’, Nirala, critical of the models of education of his times, introduces us to two ideas of education, equally futile. On the one hand is Babu Premkumar, rich, romantic, dandy, spendthrift who “had come to Lucknow to discover sophistication and urban etiquette, as is the custom these days” and had failed to pass his annual university examinations repeatedly. On the other hand, there is Shankar, a Brahmin who despite “the corrupting influence of an English education”, had remained “steadfast in defending the customs that have continued unsullied for generations.” For both of them, education has not led to the broadening of the mind or the expansion of the intellect. In ‘What I Saw’, similar ideas about education and respectability plague the protagonist Pyarelal –“Why is it impossible? Why can’t the two pursuits–of beauty and brahmacharya–go together?”

The contemporary state of writing in Hindi, also, occupies a lot of Nirala’s concern. There is the poverty-stricken condition of writers that makes playful appearance in ‘Sukul’s Wife’ when the narrator becomes “painfully aware” of his naked torso:

…if only I had something to wear. I imagined dressing myself up in all manners of expensive suits, but, in reality, there were only two dirty kurtas close at hand. I felt a seething anger at my publishers. These low-born creatures have no respect for writers.

In ‘Chaturi Chamar’, he says that Chaturi “commands immense popularity and respect, since his approach to shoemaking, like the dominant literary trends of the age, is orthodox.” In ‘Billesur Bakriha’ he writes:

There is indeed a severe drought that afflicts the land of Hindi language and literature: rasa has dried up completely. But in the everyday world of Hindi speakers, rasas flow wide and deep, like the Ganga and the Yamuna.

The stories in A Portrait of Love are tight, compact, and evince keen attention to details of craft and narration. In ‘What I Saw’, for instance, both first-person and third-person narratorial voices are commendably used for tonal effect. There is not so much mastery of plot in these seven narratives as there is a robustness and finesse in narration and an overarching vision to unravel something new, to hack at an obsolete idea or to uproot an unserviceable belief. The beginning to each story is sharply dramatic and the ending light, swift and sudden in an attempt to affect a closure that is both present and absent -- the storyteller’s last laugh at society’s stubborn incorrigibility.

In five of the seven narratives in the book, women occupy centre-stage and wrest attention and authority in multiple ways. These women are, by turns, a Muslim woman (‘Sukul’s Wife’), a widow (‘Jyotirmayee’), a prostitute (‘What I Saw’), a street-beggar (‘Devi’), and a smart, unknown college girl (who, though invisible throughout the story, thoroughly governs its plot and consequences) intending to teach a fellow-student a lesson (‘Portrait of a Lady-Love’). Even the men in the remaining two stories – ‘Chaturi Chamar’ and ‘Billesur Bakriha’ belong to the margins. What is memorable in each of these stories is the way these characters resist their marginalisation and establish themselves in the reader’s eyes as intellectually and emotionally intelligent humans deserving of love, compassion, and above all, respect.

In ‘Devi’, Nirala writes, “Considering a living person as dead, and a dead one as alive, is both a delusion and a form of knowledge. Deer and foxes take a scarecrow to be a living person, while the wise squirrels scamper about living bodies thinking they are carved in stone.” Nirala’s mission, in the seven narratives of this collection, is to jolt the dead into living, to awaken the complacent to suffer social questions, and to invoke the oppressed to seek solutions. With the unique “window into other people’s mind” that he discovered through his interactions with all and sundry, and his keen observation and analyses, Nirala encapsulates the full range of literary, political and social ideas of his times that remain pertinent even today.

In his ‘Introduction’ to the book, Choubey remarks that for English readers, the domain of Hindi-Urdu literature has remained narrow due to “the very limited repertoire of translations” and this has not only been “detrimental to the legacy of other major writers but also to the debates they stirred and the issues they championed.” His translation of Nirala is an invaluable addition to this corpus -- a veritable flag for new literary futures. His replication of these stories in English gives them not merely a new literary life and a wider readership but also helps to make Indian English more Indian by bringing it closer to the country’s vernacular soil, and to the heart of its essential complexity and plurality.

(Basudhara Roy teaches English at Karim City College affiliated to Kolhan University, Chaibasa. Drawn to themes of gender and ecology, her five published books include three collections of poems, the latest being Inhabiting. She loves, rebels, writes and reviews from Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India.)