In the Maoist-affected district of Sukma in Chhattisgarh, a political churn is taking place. “Hamare gaon mein ‘vote-wale school’ nahin tha (earlier, our village did not have a school where a polling booth could be set up),” says Sushil Podiyam, a volunteer teacher and a native of Minpa in Sukma district. He narrated how the people in his village had voted for the first time in the 2023 Chhattisgarh assembly elections. “The villagers had never seen a voting machine before; they did not know which button to press,” says Podiyam. Ganesh Salvam, of Elmagunda village in Sukma district, says: “Even senior citizens cast their votes for the first time.” When asked if they would vote in the upcoming Lok Sabha elections, both Podiyam and Salvam say that it will be decided by the villagers.

Schooling For Democracy In Naxal-Affected Areas Of Chhattisgarh

The journey of demolished schools to vote-wale schools in the Naxal areas of Chhattisgarh

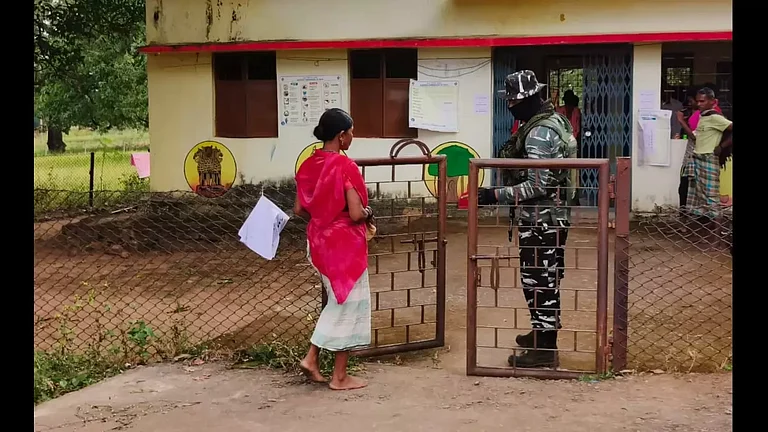

Konta constituency in Sukma district registered an eight per cent increase in voting during the 2023 Chhattisgarh assembly elections, as compared to the 2018 assembly polls. In this election, polling booths were set up—in reopened government primary schools—for the first time in Elmagunda, Tarrem, Silger and Minpa villages. These schools were demolished by the Maoists during the period of Salwa Judum—a militia group that was mobilised as part of counter-insurgency operations. They were reopened because of an initiative of the villagers in 2018. Salwa Judum was disbanded after the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in 2011.

But during these elections, the Maoists were on the warpath. Multiple violent clashes between the rebels and the security forces were reported. Many Maoist training camps were ransacked. On November 3, 2023, the Maoists killed a BJP leader during a meeting at Narayanpur, a town in Chhattisgarh. Two jawans were killed in Improvised Explosive Device (IED) blasts in Kanker and Gariaband districts in 2023. One jawan was injured in Tondamarka village in an IED blast on the day of the elections—November 7, 2023. The Maoists also issued multiple warnings to the villagers asking them to boycott the elections.

Kiran G Chavan, the superintendent of police in Sukma, says that conducting elections in these villages is very difficult. For the upcoming Lok Sabha elections, Chavan says that camps of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) have been set up in these villages, and the government is planning to hold the polls in even more sensitive villages this time.

Amidst the multiple factors that have facilitated the holding of elections in the sensitive villages of Sukma district, it is pertinent to trace the journey of ‘vote-wale schools’ where the polling booths were established.

Early 2000s…

Somru Podiyam of Kistaram panchayat in Sukma, recalls: “I was studying in Grade 3. ‘Judum’ and ‘Ghast waale’ once entered our village during daytime. My parents along with other villagers had to run away to the jungle fearing for their lives. I too had run deep into the forest. We had to camp inside the forests for a couple of days until ‘Judum’ had left. We heard gunshots throughout the day. When we returned, we found that our school building had been demolished; our huts and pigsty were ransacked.”

High concrete walls and small windows in government schools became a tactical location for Salwa Judum members and security forces to operate. School buildings were turned into barracks. It has been alleged that schools were also used to detain, torture and fire upon the Adivasi villagers who were unwilling to leave their villages for the Salwa Judum makeshift camps, where human rights abuses were rife.

In retaliation, the concrete schools were demolished by the Maoists with help of villagers. In an open letter, Ganapathy, the erstwhile general secretary of the Communist Party of India (Maoist), which was banned in 2009, justified the demolitions. The district administration estimated that around 133 government schools in the Konta region of Sukma and more than 400 government schools in Bijapur district were demolished during the Salwa Judum period. On July 5, 2011, the Supreme Court directed the Chhattisgarh government to vacate all schools and hostels that were occupied by the security forces with immediate effect.

Emergence of Residential Schools

After most school structures were demolished and the villagers shifted to Salwa Judum camps, the district administration established Porta Cabins—bamboo structures—in the vicinity of towns that acted as residential schools to enable the schooling of displaced children. Local youth were recruited as anudeshaks (instructors) to look after the children.

After the Salwa Judum was banned, while villagers from their makeshift camps were sent back to their villages, Salwa Judum members were given refuge within the security forces’ camps and further militarisation of the region continued. But Porta Cabins—sustained under the close watch of security forces’ camps—lacked educational infrastructure in the interior sensitive villages, called ‘liberated zones’ by the Maoists.

Anudeshaks were deployed in the interior villages in the south Bastar region to get more Adivasi children from interior villages to enrol in the Porta Cabins with the promise of good food, clothing, schooling and medical facilities. But most Porta Cabins started housing 600-700 children, exceeding its capacity of 500. Anudeshaks were now acting as both caretakers and teachers and were paid Rs 3,000 per month from the District Mineral Foundation (DMF) fund.

With the state mostly focused on the militarisation of the region and combat operations against Maoists, sheer apathy was displayed towards restoring the demolished educational infrastructure in sensitive villages. There were also problems in upgrading the quality of education in Porta Cabins—lack of trained teachers, boarding spaces, toilets, food and healthcare. Ironically, a huge amount of funds continued to flow from both the Centre as well as the state’s tribal ministry for these schools.

The opaque nature of this war zone led to a lack of accountability in the usage of DMF funds, and made these schools hubs of corruption. Though it is claimed that the DMF fund is regularly utilised for infra-related work in these schools, a clerk, on condition of anonymity, alleges that several crores of rupees were sanctioned for the installation of CCTV cameras from the DMF fund in Porta Cabins of Bijapur district. But no camera has been installed even after the issuance of three work orders. An RTI has been filed seeking information on the total funds used by DMF in these residential schools of Bastar Sambhag region. But no information has yet been furnished.

Moreover, multiple cases of sexual and child rights violations in Porta Cabins have been reported over the years. According to many media reports, in August 2017, girls of a Porta Cabin in Dantewada district had alleged that some security personnel had sexually assaulted them during the Raksha Bandhan celebration on the school premises. Two persons were arrested and after a trial, which went on for two years, they were acquitted of the charges by a lower court. However, a senior security official has said that the accused were handed over to the police and departmental action against them has been initiated.

In July 2023, a seven-year-old child was allegedly raped by a man in a Porta Cabin in Sukma district. A Special Investigation Team (SIT) was constituted, and the accused was jailed within a week of filing the FIR.

In February 2024, a fire burnt down the bamboo-made walls of a Porta Cabin in Bijapur district owing to a short circuit, and a four-year-old girl child was badly charred in the fire. The Porta Cabin was housing around 400 children then.

The Porta Cabins are south Bastar’s version of Canadian Indian Residential Schools and Adivasi children are admitted with the objective of ‘mainstreaming’ them. The children’s ties with their communities, festivals, and culture are snapped and they grow up under surveillance in appalling conditions in the milieu of a foreign culture. At present, Rs 1,700 is sanctioned per child per month in the Porta Cabins, but rampant corruption in the usage of this fund has been reported with no accountability. Anudeshaks are paid a salary of Rs 10,000 per month now.

Porta Cabins used to be the only option for schooling for Adivasi children of sensitive zones in south Bastar from the early 2000s to 2018. An Adivasi either had to send her child to a Porta Cabin or her child would be deemed ‘out of school’.

Reopening of Demolished Government Schools

Ashok Baghel, a local youth of Kamaram village, had completed his education till class 12 from a residential school of Dantewada after the school in his native village was demolished during the Salwa Judum period in 2006. By 2017- 18, the number of educated youth like Ashok started increasing in the sensitive villages of south Bastar. Most of these youth had turned down the offer of jobs in the armed forces as taking up those jobs would restrict them from visiting their native villages, strongholds of the Maoists. They were looking for job opportunities that would let them live in their native villages.

In 2018, Ashok submitted a proposal to reopen the demolished school in his village to the then collector of Sukma district, Jai Prakash Maurya. He asked him to get the permission from the Sangathan wale (Maoists). Ashok went back to his village and sent a message to the area commander of the Maoists to meet him, and placed his proposal to reopen the school in his village. The Maoists agreed on schools, anganwadis (child daycare centres), and Primary Health Centres (PHCs), but with two conditions: no concrete building would be built in the village, and second, no outsider would be allowed in the villages.

Ashok met the collector after approval from the Maoists. The collector then asked Ashok to mobilise other educated youth of these sensitive villages and conduct a survey of ‘out-of-school’ children. The survey showed that there were 133 schools that were either closed or demolished and there were around 2,100 ‘out-of-school’ children in these villages.

In 2018, Maurya mobilised DMF funds and asked the villagers to build a thatched hut for the school. He appointed youth who had passed 12th standard as shikshadoots (volunteer teachers) with a fixed pay of Rs 5,000. Finally, 55 closed and demolished government primary schools were reopened in Maoist stronghold villages of Konta region in Sukma in 2018. By the next year, the number of reopened schools increased to 93, with the enrolment of around 4,000 children. Shikshadoots were oriented on the basics of teaching for one and a half months and were deployed in schools. Shikshadoots face atrocities from both sides. While many shikshadoots have been harassed and detained by forces while they are on duty, Maoists have killed a few of them on charges of being ‘police informers’. At present, shikshadoots earn a salary of Rs 10,000 per month.

COVID-19 Period (2020-2021)

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the south Bastar region witnessed rampant dropouts of teenagers from Porta Cabins. There are multiple reports that adolescent children had taken up construction jobs in nearby suburbs or had migrated to Andhra Pradesh to work in the chili fields and never came back to school.

After the schools reopened in 2021, enrolment in Porta Cabins dropped drastically, while enrolment in reopened government schools of Sukma district started increasing. Reduced enrolment in Porta Cabins meant reduced money flow. Several education officials allege they were forced to ask shikshadoots to bring children from reopened government schools to be admitted to Porta Cabins.

The emergence of reopened schools in south Bastar is an outcome of an initiative to restore normalcy taken by locals to bring the State and the Maoists on the same page and let children continue their schooling. During COVID-19, reopened schools served as centres to stock and distribute relief to the villagers. Health workers also used the school premises to administer the vaccination drive. Shikshadoots, education officials, and NGOs now frequently interact with villagers on multiple issues of the school and the Right to Education Act. Decades after facing only atrocities from both parties, the villagers have finally got a taste of good governance.

The reopened schools are today generating a rights-based awareness among the locals. They have been vocal about their demands related to schools, staging democratic protests, and participating in elections. These schools now double up as polling booths and shikshadoots are involved in election duties.

The collector of Sukma district, Haris S, says, “Locals had come to us with the demand for schools. We complied with their demands. It’s not that we are winning over Maoists only by force, we are also gaining their trust through development.”

Recently, a press release was issued by the Dandakaranya special zonal committee of the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist) and signed by its spokesperson, ‘Vikalp’, that asked the State to create suitable conditions for peace talks. The note states that the Maoists welcomed the building of schools, hospitals and anganwadis in their strongholds. This is the first time that an official press note has been issued by the Maoists to allow schools in their strongholds.

Reopened schools were initiated in the region after a ‘silent agreement’ between the State and the Maoists. Recent statements by both sides have made this agreement official. This is an exemplary example of schools acting as peace-building institutions.

But there are problems. Three children, including a six-month-old infant, died during a crossfire between the security forces and Maoists, and one was severely injured in an IED blast set off by the Maoists in January 2024. A 12-year-old hearing and speech-impaired girl was allegedly raped and killed in Gangaloor village of Bijapur district in March, 2024, and was produced as a slain Maoist cadre to the media.

In an encounter on April 16, 2024, in Kanker district, a 17-year-old hardened Maoist cadre was killed, along with 29 cadres, thus highlighting the fact that Maoists are still using children as soldiers. At the same time, the extent of participation in democratic processes is still a challenge, though the local people have taken part in democratic protests and elections. During the Lok Sabha elections, when voting took place on April 19, 2024, there was a drastic decline in the number of votes cast.

During the 2023 assembly elections, 13.35 per cent of voters in Minpa and 47 per cent of voters in Elmagunda had participated in the elections. But in the Lok Sabha elections, only four per cent of the voters in these villages cast their votes.

The State and Maoists should hear the voices of the local people striving for peace and sustainable development. While the State should move ahead with its development initiatives, the Maoist leadership should give up its violent agenda.

(Views expressed are personal)

(Goswami is a campaigner for disarmed schools and safe childhoods in war zones and Shivhare is an independent journalist based in Chhattisgarh)

- Previous Story

‘Staying Out Of Power Has Made Congress Desperate’: PM Modi Slams Rahul Over ‘Country On Fire’ Remark

‘Staying Out Of Power Has Made Congress Desperate’: PM Modi Slams Rahul Over ‘Country On Fire’ Remark - Next Story