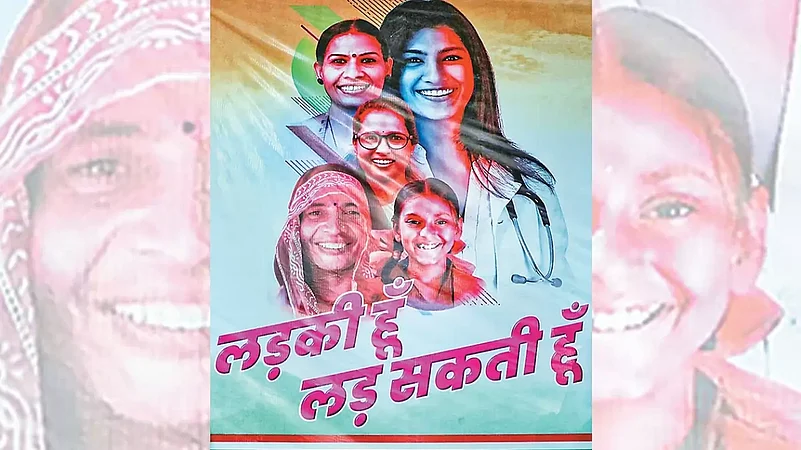

A rape survivor’s mother, an anganwadi worker, a Muslim women’s rights activist, a Dalit beauty pageant winner - the Congress party’s list of candidates in the 2022 Uttar Pradesh Assembly elections seemed to tick all the right boxes when it came to women’s representation. Living up to its promise of offering 40 percent reservation in tickets to women, the Congress party, under Priyanka Gandhi’s flagship campaign ‘Ladki Hoon Lad Sakti Hoon’ fielded 148 women candidates - a first for any party. However, only one of the 148 candidates faced an electoral win. The rest, including the star candidates, failed to even muster 3,000 votes each.

‘Ladki Hoon Lad Sakti Hoon’: True Commitment To Women's Empowerment Or A Failed Poll Sop?

It takes more than making a rape survivor’s mother, an anganwadi worker, a Muslim women’s rights activist and a Dalit beauty pageant winner party candidates to make a strong statement vis a vis women representation, writes Rakhi Bose

What went wrong?

In her 1998 paper titled “Greater Political Representation for Women: The Case of India,” feminist scholar Leela Kasturi noted that “Gender acts as an important variable in social and political structures, movements, and events. Under numerous circumstances, gender has been sought to be used as a symbol by different forces representing different philosophies at any given time.”

And yet, women’s representation in India’s public and political sphere in the first five decades after independence was minimal. Noted scholar Gail Omvedt wrote in 1987 that the “the exclusion of women from political power has been marked more than their exclusion from “productive” work or even property rights.”

ALSO READ: Bharat Jodo Yatra: Poised To Make A Mark

It was only after the reservation politics of the 80s that the question of women as voters and political representatives came to the fore once again. While the Indian Parliament and political parties have remained at an impasse over the issue of women’s reservation to safeguard political representation, the UP elections saw Congress promising unprecedented reservation to women.

“It was definitely a bold move,” Diksha Yadav, a consultant working with the Congress’ Himachal Pradesh election campaign tells Outlook. “All parties claim to work for the welfare of women and increase representation. But the Congress went one step forward and approached women not just as a vote bank but as a bankable poll plank and potential leaders,” Yadav?adds.

This is not the first time, however, that the Congress has fielded women in UP. But as past trends show, simply increasing the number of candidates may not necessarily translate into electoral gains. In 2007, the Congress fielded 37 women in the Assembly elections but only one could win. Twelve out of the 16 women fielded by the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) ended up winning the MLA badge.

In 2002, once again, only two of the 34 women candidates fielded by the Congress won. It was the highest women’s representation by any party in that election. However, 14 of the SP’s 29 women candidates became MLAs.

One of the primary arguments against providing reservation to women is that they provide an “extension to dynastic politics” in women. In India, women candidates who are “political heirs” such as Indira Gandhi attained political stardom. But, as Omvedt notes in her 2005 article in Economic and Political Weekly entitled ‘Women in Governance in South Asia,’ “at the local level, studies show that traditional pictures of ‘women’s place’ are as strong as ever and women are seen as less politically capable than the men of their families”.

While the bringing in of women in massive numbers at local governance institutions has helped change that image in the last few decades, it was only after women started emerging as an important ‘silent’ vote bank that political parties at the national level started taking women’s representation seriously.

In 2010, women voters outnumbered men for the first time in Bihar and the trend has continued since. These women are said to play a massive role in the Janata Dal (United) (JD(U))’s success in Bihar and form the backbone of Nitish Kumar’s core voter base. “The Congress wanted to convert this ‘invisible vote bank’ into visible political players,” Yadav?states.

Sources close to the campaign state that it grew from Priyanka Gandhi’s own personal experiences as a woman leader. The list of candidates the party chose for the ‘Ladki Hoon Lad Sakti Hoon’ campaign also shows the party’s caution in going against dynasty politics. “We chose leaders from within the Congress party’s women cadres and those who we thought had some kind of social impact,” a Congress leader campaigning in Unnao for Asha Devi, the mother of a rape survivor, had told Outlook ahead of the elections.

Asha Devi herself had expressed her gratitude at being selected and had promised to work for the betterment of women’s safety, if elected. Asha Devi polled less than 3,000 votes but her daughter said they had not lost hope. “I will be contesting in 2027,” the survivor proclaimed.

An enthused cadre alone, however, may not lead to electoral results. According to Lucknow-based writer and political observer Virendra Yadav, one of the reasons why the ‘Ladki Hoon Lad Sakti Hoon’ campaign failed to work was its missing connect to ground realities.

“While the campaign itself was very forward-thinking and set new standards for political parties in terms of women’s representation, the Congress failed to provide the infrastructural and institutional support a campaign of such high risks and stature needed,” Yadav tells Outlook.

He agrees that women in the state are looking for alternatives but adds that the Congress campaign, though a popular and catchy catchphrase on social media and in elite, educated circles, failed to permeate to women across intersectionalities.

“The party fielded a Dalit face who is popular on social media or a social worker who is known among certain circles. But how do they address the issues of Dalit or underprivileged women in neglected parts of the state? The campaign provided barely any blueprint for that.”

Yadav adds that the Congress lacked cadres-based local campaigning or organisational planning in that aspect, meaning that “despite best intentions, their message failed to reach the masses.”

This is one aspect in which the BJP may have beaten the Congress as well as the Samajwadi Party (SP). “The growing Labharthi factor cannot be ignored. Most voters from underprivileged sections don’t vote for long-term empowerment goals or idealism. They vote for immediate gains,” he says. In that sense, the promise (and delivery) of rations and other freebies might appear to be a more attractive option than a lofty slogan about empowerment.

“The problem is the internal corruption and mismanagement of the Congress party,” alleges Priyanka Maurya, BJP leader who was formerly the face of the ‘Ladki Hoon Lad Sakti Hoon’ campaign. Disillusioned after being denied a ticket, Maurya, a homeopathic doctor, quit the Congress in January in the run-up to the polls and joined the ruling party. “Their campaign was over that day itself when I quit,” Maurya claims.

The leader alleges that the party gave out tickets on the basis of bribes and political favours. She also says that party leaders used the popularity of local leaders and social workers to promote the campaign but did not really care about the women on the ground. “Only those with political clout or money can move ahead in the Congress. Their idea of women’s empowerment is a farce,” she claims, adding that Priyanka Gandhi herself was aloof from the real problems of women in UP or even the concerns of women leaders within the Congress. “She barely met us,” Maurya alleges.

A Congress leader, on condition of anonymity, says that the reason Gandhi was not actively campaigning door-to-door in Uttar Pradesh was that the party did not want to restrict her to just the state. “The party wants to project Priyanka Gandhi not just as a face for UP but as a pan-India leader,” she says. Though some party leaders remain cagey discussing the campaign, others are hopeful. “Yes, the campaign did not work in UP but there are many reasons for that. UP politics are riven with caste and class. Perhaps the Congress’ strategy lacked some foresight in that regard. But that does not mean that Congress will not champion women’s empowerment anymore,” a Congress spokesperson tells Outlook. With the elections in Himachal Pradesh and Gujarat, the focus of women seems to have diminished to a bare minimum. The ‘Ladki Hoon Lad Sakti Hoon’ campaign has failed to make it to the poll pitch in either state. Yadav says that this should not be read as a failure of the campaign but rather of the Congress’ execution of it. “Hopefully, others will learn lessons, see this as an avenue to explore, rather than relegate it to being just a failed experiment,” he opines.?

(This appeared in the print edition as "Women’s Representation")

- Previous Story

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana - Next Story