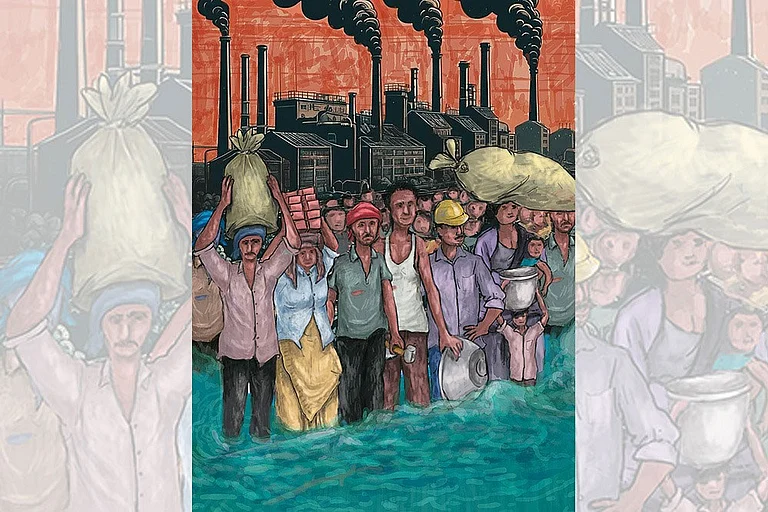

In the relentless march of headlines detailing heat wave fatalities—“100 People Die in Heatwave” or “Extreme Heat Kills Hundreds”—the profound human narratives often fade into statistical obscurity. Who are these individuals succumbing to the sweltering temperatures in the Global South, in our cities, and across our villages? What stories do they carry, and what societal injustices push them to the forefront of this climate crisis?

An Unequal Heat: In Photos

Dalit women working as farm labourers bear the extreme brunt of the climate crisis and escalating temperatures. This visual project documents their stories, which are a powerful testament to the fact that there can be no climate justice without social justice

The unsettling truth emerges: the victims predominantly hail from marginalised communities, bearing the intersectional weight of caste, gender, and economic disparity. The impact of heat waves is far from equitable.

The Heat is not Equal to All of Us

Consider someone sitting in an air-conditioned room and compare their experience to that of a Dalit woman toiling in the sun, working someone’s field for a daily wage. The difference is stark. In these fields, even access to water is unequal. In the realm of environmental discourse, water is often romanticised as the nectar of life, a symbol of purity, and a source of natural beauty. However, for Dalits in India, water carries a burden far heavier than its life-nurturing properties—it is a stark reminder of caste-based discrimination and exclusion.

Imagine fetching water not as a routine chore but as a journey fraught with the fear of facing discrimination and violence. For Dalits, accessing water sources reserved for upper castes can result in ostracisation, verbal abuse, or even physical assault. The simple act of quenching one’s thirst becomes a daily struggle.

With recent heat waves sweeping across northern India, many found themselves sick. Hospitals in Delhi saw a surge in patients coming in with heat related illnesses. According to The Indian Express, official sources reported that between March 1 and June 18, the national capital recorded 40,000 cases of suspected heat stroke. Experts have raised concerns that these numbers could be much higher, as heat-related illnesses and deaths are often under-reported.

When I ventured into a remote village in Uttar Pradesh for my visual project ‘Heat South Asia’, I met Kamlesh, a Dalit woman labourer. Her voice was frail but resolute as she recounted her struggle: “I have been sick for at least three days now because of this heat. I have lost work and daily wages because of it. I earn Rs 350 ($4) per day working as a labourer on farms. In the past four days, I’ve lost over Rs 1000 (around $11) due to the heat and related sickness.”

The project began in February of last year, spurred by personal moments with my grandmother. She would come to stay at our home in the city because the heat in the village became unbearable. Both of us, born into the “lower” caste, are deemed untouchable in the rigid caste hierarchy that has governed Indian society for over 3,000 years. Listening to her stories from the village, my focus shifted to Dalit women in rural India—women who are generationally caste-oppressed and toil in the fields as farm labourers.

I met and photographed women, already marginalised by gender and caste, who now stood at the forefront of the climate crisis and its escalating temperatures.

We are at an epochal moment in the world’s climatic history. India is witnessing some of the highest temperatures ever recorded, with over a hundred deaths in a single month in North India.

Within this searing reality, the women working on the farms endure the extreme brunt of the heat. Due to pervasive caste discrimination, they are vulnerable not just socially but also climatically.

At times, in air-conditioned conference rooms where fervent discussions on environmental sustainability echo, there exists a curious reluctance—a hesitancy to peel back the layers of complexity and acknowledge the stark reality of caste dynamics in the current climate crisis. Coupling that with gender is almost absent. Perhaps it stems from discomfort, a fear of stirring the hornet’s nest of social hierarchy, or a misconception that environmentalism is a neutral ground untouched by the tendrils of caste.

However, as I delve into the depths of environmental issues plaguing the Indian subcontinent, it becomes increasingly evident that omitting the discourse on caste is akin to trying to understand a puzzle with a crucial piece missing.

Caste, deeply entrenched in the social fabric of India for centuries, is not merely a relic of the past but a living, breathing entity that permeates every aspect of society, including its environmental landscape. From access to resources to patterns of land use, caste influences every step of the environmental journey, often silently dictating who benefits and who bears the brunt of ecological degradation. To truly unravel the complexities of environmental challenges in India, we must confront this reluctance head-on.

I also found while shooting in villages and within Delhi that women engaged in informal labour are susceptible to health issues exacerbated by heat exposure, including pregnancy complications, urogenital ailments like urinary tract infections (UTIs) and rashes, as well as conditions such as fevers, sunburn, dehydration, and fatigue.

Amongst it all caste discrimination not only attacks selfhood and dignity, effectively dehumanising communities, but also results in a lack of resources. In this case, the most crucial resource is land. Without land ownership, these women work as contract laborers on farms, subjected to another hierarchy with the farm owners.

Kamlesh’s story is a window into the lives of the women. She wakes before dawn, her body already aching from yesterday’s labour, to prepare for another gruelling day in the fields. The heat is relentless, oppressive, and unforgiving.

It seeps into her bones and saps her strength.

The small earnings she makes are crucial for her family’s survival, yet the rising temperatures threaten to take even that away.

Each day lost to heat-induced illness is a blow to her fragile economic stability.

In photographing women already marginalised, I seek to challenge the mainstream representation of Dalits. There is a preconceived notion of what a “Dalit” or “vulnerable marginalised person” looks like, captured within a gaze that reiterates their oppression.

While documenting how women combat the increasing heat and devise their own solutions as the planet warms.

The project started with an urge to dismantle the imagery often associated with those at the margins, informed by my own lived experience as a Dalit woman and a photographer.

The small earnings kamlesh makes are crucial for her family’s survival, yet the rising temperatures threaten to take even that away.

Last year, the first heatwave struck the country in February—a time when one would generally expect cooler weather and the comfort of sweaters. This unseasonable heat wave prompted my grandmother, Omi, who hails from western Uttar Pradesh, to stay with us in Delhi. The heat in her village was unbearable, exacerbated by almost no electricity. Forget about air conditioning.

During this period, I travelled with her and began photographing women, mostly Dalit women, working as farm labourers. They work these fields because they lack their own land. Dalits, historically, own little to no land. In the middle of it all, unseasonal rains added another layer of hardship, compounding their struggle.

This year, as the heatwaves continue, I find myself once again documenting the lives of these women. Their stories are a powerful testament to the fact that climate justice cannot exist without social justice. The heat does not impact us all equally; it disproportionately burdens those already marginalised by society.

These women, who toil in the sun for a meager wage, represent the human face of climate change. They endure the brunt of the heat, their lives a daily struggle for survival. Their stories remind us that the fight against climate change is also a fight for equality and justice.

As I continue my work, photographing and documenting their lives, I am driven by the urgency to make their voices heard. In their resilience and strength, I see the embodiment of a powerful truth: there can be no climate justice without social justice. And until we recognise and address the deep-seated inequalities that fuel this crisis, the headlines will continue to obscure the human cost of our changing climate.

While on this visual documentation project—even the word ‘‘heat’’ I have come to realise, is more than just rising temperatures. It is also a metaphor for a simmering, potent force. For centuries, women, particularly those marginalised and oppressed, have known this heat intimately. It is not merely about the weather, but also a deep-seated rage—a fury borne from centuries of subjugation. For women like Kamlesh and me, relegated as ‘untouchable,’ heat embodies more than discomfort; it is a symbol of our resistance in the face of systemic oppression. Through their stories and my lens, I hope to convey this enduring resilience and the quiet, steadfast defiance that defines their lives.

(This appeared in the print as 'An Unequal Heat')

Bhumika Saraswati is a Delhi-based independent journalist, photographer & docu filmmaker working on the long-form visual project @heat.southasia

- Previous Story

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana - Next Story