The contempt petition filed against the Secretary, Department of Justice of the central government before the Supreme Court (SC) has simply brought into the open a tussle between the Executive and the Judiciary contemplated by the Constituent Assembly and has been going on ever since.

Appointment Of Judges: Why Collegium System Is The Only Hope We Have Against Authoritarian Rule

With much criticism directed against the courts with regard to judicial appointments, there may be reasons for preserving the Collegium system as it stands today

There is no gainsaying that vesting the power of appointment of judges in the judiciary to the exclusion of the political executive comes with its own failings and misgivings. There is also no doubt that the law that was laid down by the Supreme Court—the Second Judges case—that the appointment of judges, though made by the president, has to be with the concurrence of the CJI and his or her senior most puisne judges, with no control being left to the political executive, was actually contrary to both the letter and the stated intent of Article 124 of the Constitution. Article 124 requires only ‘consultation’ with the CJI by the president, not his or her ‘concurrence’. The need for ‘consultation’ to be replaced by ‘concurrence’ was emphasised by several members of the Constituent Assembly during the debate on the draft of the Article. But rejecting this viewpoint, Dr BR Ambedkar, when explaining the intent of the Article, had said:

“I personally feel no doubt that the Chief Justice is a very eminent person. But, after all, the Chief Justice is a man with all the failings, all the sentiments and all the prejudices which we as common people have; and I think, to allow the Chief Justice practically a veto upon the appointment of judges is really to transfer the authority to the Chief Justice which we are not prepared to vest in the President or the Government of the day. I therefore, think that is also a dangerous proposition.”

Despite this, the Supreme Court, in 1993, in the Second Judges case abrogated this power unto itself and read ‘consultation’ as ‘concurrence’, reducing the role of the president and, therefore, of the political executive to a mere rubber stamp. But the alternative that exists, brings to life today some of the fears expressed in the Constituent Assembly back in 1949, of political interference in the process of appointments, rendering the Supreme Court and the high courts—protectors of the fundamental rights of the people against wanton exercise of State power—subservient to the political executive. The basis of the decision of the drafting committee of the Constitution in vesting the power of appointment of judges in the political executive is reflected, once again, in the words of Dr BR Ambedkar, who, when opposing an amendment that sought to make it a provision of the Constitution that retired judges of the Supreme Court would not be eligible to hold any other office of profit under the Government of India or any state government, had said:

“The judiciary decides cases in which the Government has, if at all, the remotest interest, in fact no interest at all. The judiciary is engaged in deciding the issue between citizens and very rarely between citizens and the Government. Consequently, the chances of influencing the conduct of a member of the judiciary by the Government are very remote...”

This was clearly an error of judgement. The working of the Constitution has shown us that the government is the most frequent litigant in the courts, and battles for the rights of the people are invariably fought between the government and its citizens. This fact was recognised by the Supreme Court in the National Judicial Appointments Commission case and was one of the reasons for striking down the proposed NJAC--, which had included political participation in the appointment of judges. Therefore, the basis on which primacy was given to the political executive in matters of appointment of judges, as well as the reason why granting of post-retirement positions was permitted, have proved to be completely flawed. Yet the number of positions available for judges post-retirement for the government to hand out in its discretion has only increased with the increase in the number of specialised tribunals headed by retired judges today.

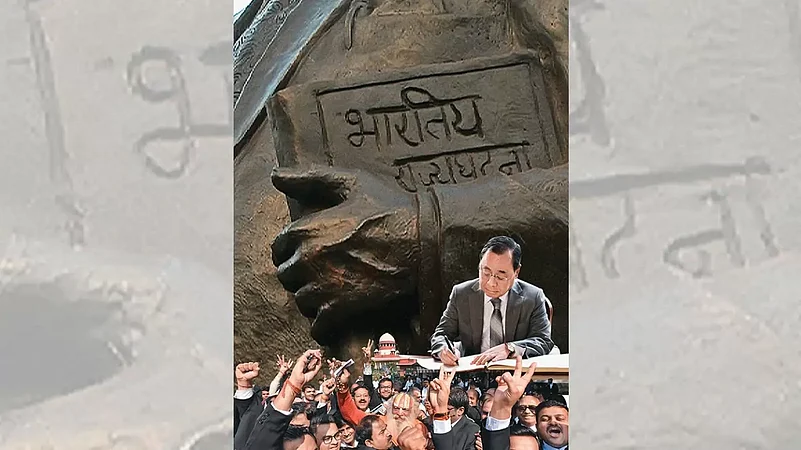

Post-retirement appointments are a possible inroad into the independence of the judiciary that strikes at the heart of the legal maxim that justice must not only be done but should be seen to be done. The absolute trust that the people of India repose in the Supreme Court is best seen in the Babri Masjid case, that sharply divided the opinions of the entire nation. Yet the verdict of the court was accepted peacefully by all parties. In a case such as this, no one ought later question the decision on the basis that soon after pronouncing the judgement, Mr. Ranjan Gogoi, the then CJI who had presided over the 5-judge bench that decided the case, retired and immediately accepted a nomination from the political executive as a Member of Parliament in the Rajya Sabha. There are many such instances of eyebrows raised at judges criticised during their tenure for upholding the actions of the government against sound jurisprudence and judicial precedent and being given important positions after retirement. The purpose here is not to question the integrity of any individual but simply to say that this raising of eyebrows is by itself a failing of the judicial system that we need to safeguard against.

Although the role of the political executive was reduced to a minimum by the court’s 1993 verdict, it continues to assert its influence, most egregiously, by returning names recommended by the SC Collegium. This has led to delays in the appointment of judges, leading to loss of their seniority and even robbing them of the opportunity to rise within the ranks. In more grave instances, this has led to eminent lawyers recommended by the Collegium never finding their way to the bench, and judges of high courts retiring without elevation to the SC. Justice Akil Kureshi’s name reportedly being rejected by the central government for appointment as Chief Justice of the MP High Court, the name of Justice KM Joseph being reportedly returned by the government for elevation to the SC the first time it was recommended by the collegium and the widely reported rejection of the name of former solicitor general, Gopal Subramanium, for elevation to the SC are just some of the better-known instances. The dots connected by news reports at the time were that Justice Kureshi had remanded then State Home Minister Amit Shah to police custody in 2010 in the controversial?Sohrabbudin fake encounter case. Justice Joseph, as the Chief Justice of the Uttarakhand High Court had set aside President’s rule imposed by the Modi government in the state in 2016, and Mr. Gopal Subramanium had been amicus curiae?in the SC in the Sohrabbudin fake encounter case.?Irrespective of what the truth of these instances may be, what is dangerous is the corrosion of people’s faith in the system of judicial appointments that accompanies each such instance. The ongoing contempt is concerned only with the power of the central government to return names twice recommended by the Collegium. This will be decided by the SC in these proceedings but the problem is larger.

No doubt the present system of appointments is not immune to political influence. Far from it. But it is equally true that the entire judiciary cannot be replaced in a day, a year or even a decade. Judges of high courts appointed today will remain in the system for close to two decades and the fate of one government will often be decided by judges appointed during the tenure of another. Also, while political influence is, and will remain, one of the factors at play, there are a multitude of other factors that play a role and which dilute the political affinity of judges.

Therefore, it is nobody’s case that the present system of appointment of judges by the judiciary to the exclusion of the political executive is a perfect system. Let there be no doubt that this is merely the lesser of two evils. But as majorities in the legislature have become absolute and power has become concentrated in the hands of one party, judicial appointments by the judiciary, even with all its opaqueness, nepotism and biases, is the only hope we have against authoritarian rule. Where we are today is best summed up in the words of Prof KT Shah speaking in the Constituent Assembly in May 1949, when he said:

Advertisement

“In my opinion, Sir, if I may say so with all respect, this Constitution concentrates so much power and influence in the hands of the Prime Minister in regard to the appointment of judges, ambassadors, or Governors to such an extent, that there is every danger to apprehend that the Prime Minister may become a Dictator if he chooses to do so. I think there are cases which ought to be removed from the political influence, of party manoeuvres. And here is one case,?viz.?Judges of the Supreme Court, who I think should be completely outside that influence.”

(This appeared in the print edition as "The Last Bastion")

Advertisement

(Views expressed are personal)

Mohammad Nizam Pasha is a lawyer practising in the Supreme Court

-

Previous Story

Kolkata Doctor Rape-Murder Case: Victim's Father Turns Down Compensation, Says 'I Want Justice'

Kolkata Doctor Rape-Murder Case: Victim's Father Turns Down Compensation, Says 'I Want Justice' - Next Story