June 25, 1975. It was around 9 pm. Delhi’s Ramlila Maidan was flooded with people. The sweltering heat was not a bar. The capital city was yet to imagine a metro. People walked for miles, piled into DTC buses and rode cycles to reach the protest venue. Their demand was unequivocally clear—‘Indira, step down’.

Emergency To Now: Coming Full Circle in Politics

Bans and arrests then, bans and arrests now. We have come full circle, say political experts

On the stage were Morarji Desai, who came out of retirement to fight the allegedly corrupt Congress government in Gujarat run by Chimanbhai Patel; Raj Narain, whose plea led to the controversial Allahabad High Court judgement that banned Indira Gandhi from fighting elections for six years; RSS pracharak Nanaji Deshmukh; Delhi Jan Sangh leader Madan Lal Khurana; and Jayaprakash Narayan (JP) who demanded a “total revolution”. Addressing the cheering crowd, JP read out Ramdhari Singh Dinkar’s poem: ‘Singhasan khaali karo/Janata aati hai’ (Leave your throne, people are coming)

A few km from the Ramlila Maidan, a different script of Indian democracy was being drafted. Around the afternoon, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, along with West Bengal Chief Minister Siddhartha Shankar Ray, met President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed and informed him about the decision to impose the national Emergency. Except for a few close aides of Indira Gandhi and her son Sanjay Gandhi, nobody in the Cabinet was aware of it.

Elsewhere, at Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, in the office of The Indian Express, things were heating up. Journalist Coomi Kapoor, who later wrote the book ‘The Emergency: A Personal History’, was asked to check why there were frequent power cuts.

Nobody was prepared for what was going to hit them.

In the middle of the night, the police started knocking at the doors of ‘listed’ Opposition leaders. The plan was to arrest all of them at once so that they don’t get a chance to escape or plan anything, reminisces Kapoor in her book.

Around 1:30 am, the police reached the Gandhi Peace Foundation where JP was staying. K S Radhakrishnan, who attended to the police, requested them to wait for a while, saying JP was not well and needed uninterrupted sleep. But his health was not a concern for Indira Gandhi’s police. At 3 am, he was taken to the Parliament Street Police Station. The news of JP’s arrest spread fast. A few press people and JP supporters reached the police station. Waving to a small gathering, JP thundered: “Vinaash kale vipareeta buddhi (People lose their minds as they inch closer towards their end).”

While JP and Desai were arrested that night, two other tall leaders of the Opposition, Atal Behari Vajpayee and Lal Krishna Advani, were in Bangalore. The next day, around 7:30 am, when they got to know about the previous night’s arrests and found out that the police were approaching to arrest them as well, they issued a press release, which said that June 26, 1975, will be remembered in history as August 9, 1942, when MK Gandhi called for the Quit India movement against the British. Advani wrote in his diary: “June 26, 1975, may well prove to be the last day in the history of Indian democracy as we understand it. Hope this fear will be proved unfounded.”

Soon after his arrest, Vajpayee’s health started deteriorating. He was sent to the AIIMS. No one except his foster family—the Kauls—were allowed to meet him, and even these meetings were held under surveillance.

After a few days, when Vajpayee was sent back home and kept in confinement, his foster family could hardly visit him. The fear of being seen with the Kauls was so profound that taxi drivers would deny them rides. In her book, Kapoor quotes Vajpayee’s foster daughter Nirmala Bhattacharya who later recalled: “We were treated as untouchables.”

Notably, most of the arrests were made prior to the proclamation of the Emergency. The leaders were not even aware of the grounds of their arrests. The next morning, at 8 am, the strident voice of the prime minister pierced through the prevailing silence. The All India Radio news bulletin turned out to be the declaration of the Emergency: “Brothers and sisters, the President has declared a national Emergency. However, there is nothing to fear. You must be aware of the conspiracy that has been hatched since I took some progressive steps for the people of India... They are not letting the elected government work,” the voice said.

Notably, most of the arrests were made prior to the proclamation of the emergency. The leaders were not even aware of the grounds of their arrests.

This four-and-a-half-minute declaration was preceded by a gazette notification from the President of India that read: “In exercise of the powers conferred by Clause 1 of Article 352 of the Constitution, I, Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, the President of India, by this Proclamation declare that a grave Emergency exists whereby the security of India is threatened by internal disturbances.”

It was also accompanied by a notification under Article 359 that suspended the fundamental rights of the citizens enshrined under Articles 14, 19, 21 and 22. The newspapers were subjected to pre-censorship. They took away the right to protest and precisely, the rights of the Opposition to voice their concerns against the government. The RSS and Jamaat-E-Islami Hind were banned for allegedly fomenting communal sentiments. It was followed by the arrests of journalists and Opposition leaders.

***

Forty-nine-years later, the government of India, on July 11, 2024, through a gazette notification, published another declaration. This time, it declared June 25 as ‘Samvidhaan Hatya Diwas’ to “pay tribute to all of those who suffered and fought against the gross abuse of power during the period of the Emergency and to recommit the people of India to not support in any manner such gross abuse of power, in future.”

While sharing the notification on his X handle, Union Home Minister Amit Shah wrote: “On June 25, 1975, the then PM Indira Gandhi, in a brazen display of a dictatorial mindset, strangled the soul of our democracy by imposing the Emergency on the nation. Lakhs of people were thrown behind bars for no fault of their own, and the voice of the media was silenced.” He also added that this day will “commemorate the massive contributions of all those who endured the inhuman pains of the 1975 Emergency”.

Interestingly, the notification came a month after the election results in which the BJP lost the absolute majority in Parliament for the first time in its 10-year tenure. Political analysts have attributed the revival of the Congress that got 99 seats—formidable enough to legitimately gain the position of leader of the Opposition—to their evocation of the Constitution. The image of Rahul Gandhi holding the slim red coat pocket edition of the Constitution in all his public rallies became a centrepiece in the electoral discourse that seemingly restored the balance of power in Parliament.

On the other hand, the last 10 years of the Modi government have been criticised by the Opposition for its alleged role in the arrests of Opposition leaders, human rights activists and journalists with an intent to muzzle their voices. Mallikarjun Kharge, the Congress president, in reference to the government notification, wrote on X: “Mr Modi, BJP-RSS wants to abolish the Constitution and implement Manusmriti. So that the rights of Dalits, tribals and backward classes can be attacked! That is why he is insulting Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar by adding the word ‘murder’ to the sacred word ‘Constitution’.”

As the BJP continues evoking the Emergency, one can ponder on how this political event changed the trajectory of the party forever. Advani, in one of his speeches, said that it was the Emergency and the JP movement of the 1970s that helped the BJP overcome the persisting ‘political untouchability’. It is seemingly true as after Indira Gandhi’s assassination and the consecutive ban on the RSS, the Hindu right wing couldn’t find much space in the Indian political scenario. According to Arvind Rajagopal, the New York University-based scholar of media and cultural studies, “JP Narayan’s endorsement of the RSS as a democratic and nationalist organisation in 1977, i.e. after the national elections were announced, overturned a longstanding practice of excluding the RSS as an essentially antinational organisation.”

Pointing out how the RSS tried to complement its absence in the anti-colonial struggle through this movement, he says: “The participation in the Janata government allowed the RSS and later the BJP (formed after the exit of the Jana Sangh that led to the collapse of the Janata Party government) to claim a role in the national struggle, which it had no record of doing until that time. This became a replacement for the RSS’s absence in the anticolonial movement and accordingly, the ‘people’s struggle’ against the Emergency.”

However, research shows that the claims of the RSS as the major force have been much ‘exaggerated’. Rajagopal says that they participated fully only after the elections of 1977 were announced. The contested past brings in different history/histories. After the Emergency was imposed and the RSS was banned, the RSS chief, Balasaheb Deoras, wrote a letter to Indira Gandhi from Yeravada Jail in Poona. In the letter, he promised that his organisation “would be at the disposal of the government for ‘national upliftment’ if the ban on the RSS were lifted and its members freed from jail”.

Though it is true that several RSS leaders were arrested, and their news bulletins—Lok Sangharsh and Jana Vani—played a role in spreading the words of the Opposition leaders, it was mostly the sterilisation campaigns of Gandhi that led to her fall in the North. Even in the 1977 elections, the Congress won four states in the South.

Criticising the anti-democratic nature of the Emergency, political scientist Ajay Gudavarthy says: “The Emergency was a reminder of the violation of human rights. But does this mean that the BJP respects human rights? Home Minister Amit Shah issued a statement sometime back saying human rights are alien to Indian civilisation. Read this statement of Shah, it only looks like invoking the Emergency is only to normalise violation of rights and justifying the excesses under the Modi regime, which has often been referred to as an ‘undeclared Emergency’.” He emphasises the revisions in the Constitution sought by the BJP leaders in the past and says that it began under the Vajpayee regime with the Justice Venkatachaliah Committee that made its recommendations, but they did not move further.

***

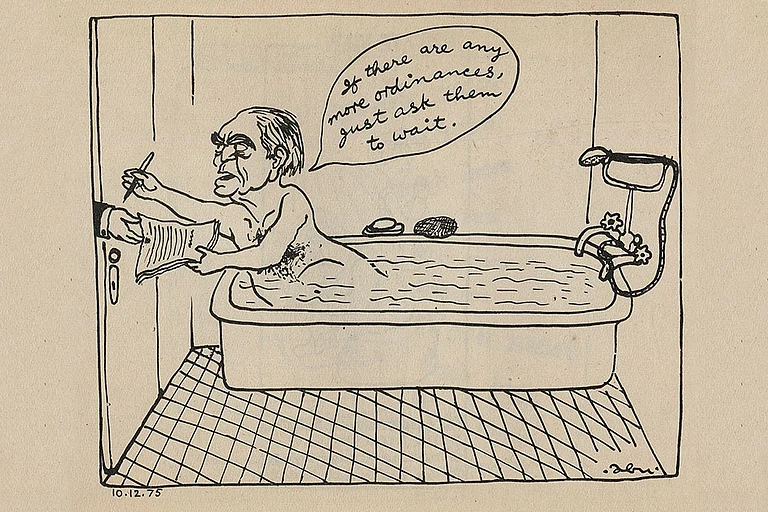

Whatever the role of the RSS might be, the muzzling of the media exposed the intensity of the Emergency. Then Information and Broadcasting Minister I K Gujral, who later became the prime minister of the country, was immediately removed by Sanjay Gandhi for not toeing the line of the government. His offence was not live-telecasting the boat club rally of Indira Gandhi and showing bits and pieces of the JP rally of June 25. In place of Gujral, Indira Gandhi deployed her confidante V C Shukla, who immediately called up the “Delhi editors for a meeting and informed them in no uncertain terms that the government would not tolerate ‘any nonsense’”, writes Kapoor in the book.

By the end of 1975, 33 journalists lost their accreditation for mostly being ‘anti-establishment’. K N Prasad, a police officer on special duty, who was chosen by Shukla to keep a watch on the media, later told the Shah Commission—appointed by the government in 1977 to inquire into all the excesses committed during the Emergency—that they used to pass the accreditation through IB that was tasked with checking the antecedents of these correspondents.

For two days after the declaration of the Emergency, there was no electricity in the offices of Delhi newspapers. While most of the newspapers already toed the government line, a few stood straight against the diktats. On June 28, when The Indian Express came out with its Delhi edition after two days, in protest, it kept the place of the first editorial blank. The Financial Express published the lines of Tagore from the poem “where the mind is without fear, where the head is held high”. Though the National Herald, which was launched by Nehru, supported the Emergency throughout, it had to remove a phrase from its masthead—“Freedom is in peril, defend it with all your might”.

Foreign newspapers and agencies were asked to sign an agreement with the government to avoid what the government considered adverse reportage. When the BBC declined to sign it, its correspondent Mark Tully was given just 24 hours to leave the country. But there were several media houses that couldn’t show the tenacity to carry on with dissent. Referring to them, Advani said when the media was asked to bend, “it chose to crawl”.

Decades later, the BBC was again in the line on fire. The Indian government, ironically run by the party that opposed the Emergency tooth and nail, banned a BBC documentary on Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The Guardian published the story with a headline: “India invokes Emergency Laws to ban BBC Modi Documentary”. Rajagopal says: “In retrospect, and by comparison with BJP-led governments, the Emergency appears like a minor episode that was magnified by the freedom of the press (now a thing of the past in India) and by a lively Opposition (which is far more severely repressed now than before).”

(This appeared in the print as 'An Irreversible Dent')

- Previous Story

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana - Next Story