It is a question that will not go away. It recurs, again and again: at the time of demonetisation, when Article 370 was repealed, at the announcement of lockdown during the pandemic…. And no doubt it is the question on many minds following the recent consecration of the Ram temple in Ayodhya. How does Narendra Modi act with such seeming autonomy, cutting through layers of democratic process, with no apparent concern for the repercussions or without suffering any apparent diminution of popularity? From where does he draw his force?

Formula One: Where Does Narendra Modi Draw His Force From?

Narendra Modi is not a conventional politician, but an ideologue who draws his mandate from the promise of hyper-capitalism

Conventional wisdom within the liberal intelligentsia has it that Modi’s clout is based on his appeal as a fundamentalist Hindu leader, that the Hindutva rhetoric of historical injustice and hurt pride has turned millions of Indians into adulators of Modi and the promise he holds out for majoritarian rule. This explanation, axiomatic for many influential opinion makers and political analysts, appears only more valid in light of the recent hoopla around the controversy-ridden Ram temple.

As someone who has studied Modi’s leadership of Gujarat and socio-political shifts in post-liberalisation India, I find this to be an inadequate explanation for Modi’s unprecedented sway. Certainly, the foregrounding of religion and a massive army of Hindutva volunteers and supporters are emboldening for a leader. Yet, I do not believe that Hindutva is the driver behind the churn India is currently undergoing; it has to be considered in conjunction with another, more forceful impetus.

Hindu nationalism made its presence felt in the early decades of the 20th century, but made little headway politically for several decades. It was only in 1989 that the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won 85 seats in Parliament, signalling an upward trend which continued in subsequent years (1991: 120; 1996: 161; 1998: 182; 1999: 182; 2004: 138; 2009: 116; 2014: 282) enabling it to form governments in various states and at the centre.

The 1980s was a watershed decade in the history of the world and of independent India. In 1989, the fall of the Berlin Wall signalled the imminent collapse of the Soviet-led communist bloc and a global shift rightward. During this time, India too began to abandon its mixed, but markedly socialist economic model to remodel itself into a capitalist economy culminating in the announcement of economic reforms in 1991.

Conventional thinking in the mainstream media projects India’s economic liberalisation programme and Hindutva as two opposing tendencies. The former is perceived as being outward and forward looking, cloaked in the accoutrements of modernisation and promises of economic growth and world connectivity, while the latter is seen as being insular and primitive in outlook, peopled by saffron-robed acolytes reliving a mythical past.

According to this way of thinking, development is incompatible with Hindutva, a view emphasised and reiterated in many different ways. For instance, in 2014, media reports claimed that Modi had abandoned the anti-minority stance for which he was known since 2002 to emerge as a vikas-purush. When Yogi Adityanath won the Uttar Pradesh elections he was said to be the new face of Hindutva versus the development-oriented Modi. According to this view, a leader can manifest inclinations towards Hindutva or development alternately, but never simultaneously. At other times, the two ideas are jammed together like unmatching Lego parts. “(The BJP) is confident that it can accommodate it (the Hindutva agenda) with its development agenda without a conflict,” wrote a columnist in Firstpost).

I would argue that this construct of economic liberalisation/liberalisation-led development and Hindutva as opposites in the popular media is a false binary. In fact, as the congruence between the timeline of the ascendancy of the BJP and the onset of structural reforms suggests, economic liberalisation provided a favourable climate for the proliferation of Hindutva.

The synergy was apparent in a number of ways, but most notably in the noisy culture wars at the end of the last century in which Hindutva ideologues showcasing anxieties triggered off by the modernising forces of economic liberalisation emerged as guardians of ‘Indian culture’.

The dramatic impact of the telecast of the Hindu epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, in the late 1980s and the boost it provided to the Hindutva project has been widely acknowledged but mostly in political terms, though the serials also reflected the commercial need of advertisers in a consumerist economy for homogenised markets and identifiable symbols.

Advertising was mainly aimed at the middle class, the BJP’s traditional support base. Economic liberalisation avidly promoted the cultural values and aspirations of this class and grew its numbers, from 170-200 million comprising approximately 20 per cent of the one billion population in 1995-96 to 432 million in 2021 (30 per cent of the population) with the likelihood of doubling to 61 per cent of the total population by 2046-47).

***

India’s transition to a full-blown capitalist economy at the turn of the century took place against a backdrop of globalisation and the spread of neoliberalism. Governments, including in the developing world, were encouraged to privatise all activities including public services and invest heavily in infrastructure and gentrification for the purpose of attracting transnational funds.

Talk of ‘Shining India’ and the frequent evocation of Singapore and Shanghai as models by various regional Indian leaders in the early 21st century were connected to these global trends. They were also an acknowledgement by Indian politicians of the aspirations nursed by the Indian elite who, like the elite in many post-colonial countries, dreamed of emulating the developed west or at least their gleaming Asian counterparts.

Modi is startlingly seized of all the multifarious possibilities presented by the particular juncture at which India is poised for realising his ideological goals.

Nobody understands this consequential juncture better than Modi. As Gujarat’s chief minister, he deployed the unsettled atmosphere and the immense power accrued to him following the terrible communal violence of 2002 to push through a speedy development programme in the state (an opportunistic use of crisis which is not uncommon in neoliberal development, as Naomi Klein described in her 2007 book, Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism). His flamboyant ‘Vibrant Gujarat’ summits advertised his understanding of brand marketing in the international arena while the successful media projection of roads, highways and urban beautification projects in Gujarat cemented his reputation as a doer and a man of action.

India offers him a bigger and a more monumental stage for his gameplan.

To make sense of Modi’s approach, in my understanding, one has to think of him not as a conventional politician, but as an ideologue who draws his mandate from the promise of hyper-capitalism embedded in the opening up of the Indian economy in 1991. The promise itself with its undertow of repercussions, of mass displacement, inequality and economic casualties implies an unspoken consensus around the use of force and a willingness to sacrifice at least some democratic rights in pursuit of a developmental utopia. This, I suggest, is what provides the ballast for Modi’s authoritarianism, not majoritarianism.

Economic liberalisation accompanied by policy prescriptions and funds for upgrading and remaking physical spaces came with a tacit suggestion of a new beginning or what is now being touted as ‘New India’. The absence of any discussion on what the social and cultural contours of this New India would be or what its aesthetics should be has created a vacuum, which Modi has sought to fill with a Hindutva blueprint.

There are a number of ways in which neoliberal development advances a Hindu majoritarian agenda. The top-down struc-ture, for instance, which tends to privilege the dominant majo-rity; gentrification as the licensing of erasure; the promotion of heritage as an invitation to rewrite the past; and, the need for new public architecture, rife with cultural potential.

Modi is startlingly seized of all the multifarious possibilities presented by the particular juncture at which India is poised for realising his ideological goals. His heavy-footedness may be reminiscent of old-fashioned despots and his RSS background might place him alongside khaki-clad rule bearers. But these elements are part of a new kind of politics which draws lessons from formulas of citification, place making and branding from neoliberal economies and uses his understanding of marketing and the media-saturated atmosphere that surrounds us to produce seductive narratives.

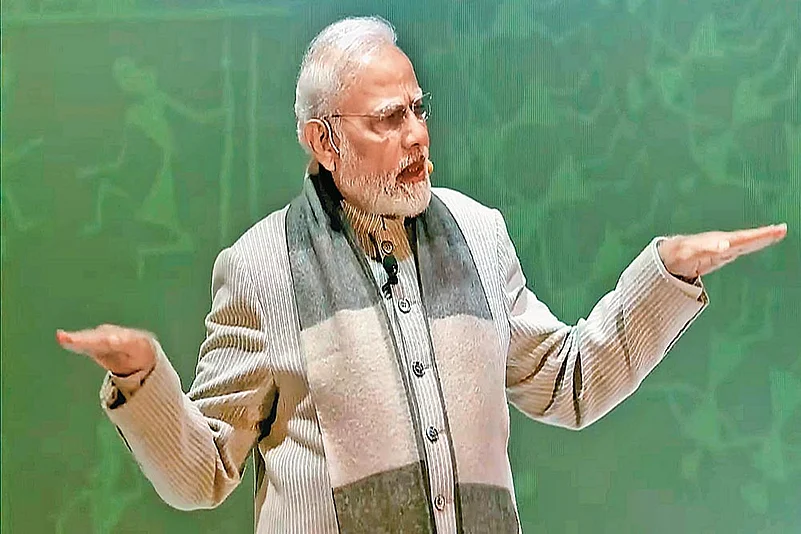

Take for instance the consciously cultivated myth of the lone figure, the singular source of diktats, the voice on the radio, the solitary figure on a beach in Lakshadweep and so on: it is for supporters of neoliberal development who prize ruthless authoritarianism and against those who fear it. It is an image that can be paternal, benevolent and threatening as required and also capable of carrying brand India on its shoulders.

One can say that Modi is a manifestation of our times even though he seems to be firmly in the driver’s seat. To try and make sense of such an amorphous entity through the lens of conventional politics is an exercise in futility. By viewing him through the tired framework of electoral contests and communal aggression, the liberal intelligentsia is failing to make sense of the phenomenon he represents or to mount a meaningful critique of it.

(Views expressed are personal)

(This appeared in the print as 'Formula One')

Amrita Shah is a Writer, Journalist and independent Scholar

-

Previous Story

RG Kar Row: Fasting Unto Death, Medics Attending 'Most Disappointing Meeting' With State Officials | Top Points

RG Kar Row: Fasting Unto Death, Medics Attending 'Most Disappointing Meeting' With State Officials | Top Points - Next Story