Food follows the way of memory. It hangs imperceptibly around us, and one does not quite know when a faint fragrance or a hint of flavour will lift us to other worlds and times. My grandparents, from Angul in Odisha and from Calcu-tta, made Ranchi their home almost a century ago. While my grandmother—Dr Pushpitabala Das, was the doctor-in-charge of the women’s section of the Indian Mental Hospital at Kanke, my grandfather—Dr Baroda Charan Das, first worked as a doctor for the government and later, with his meagre resources, started his own private clinic and a small charitable nursing home for TB patients, the first of its kind back then. My late father and my uncle doubled up as manual drip stands, while food for the patients was prepared at home.

In Retrospect: Food, Churchill & Kanke During The Raj And World War II

A personal essay of the author’s memories of the cuisine, local produce and imported food and utilities in Ranchi and Calcutta

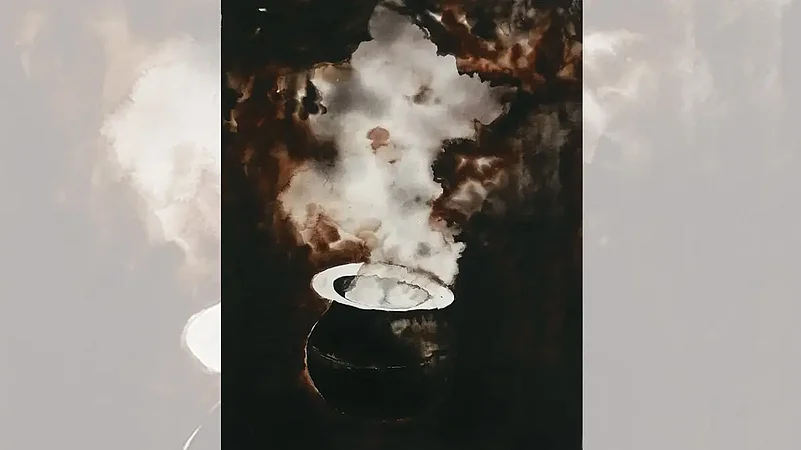

Now, what has food got to do with this little back story? For most of us, childhood and early youth memories of my father and his brother are inextricably intertwined with food, and the stories I grew up hearing about their meals, picnics or get-togethers with the extended family were steeped in eclectic aromas. The fact that my grandmother lived in Kanke, on the outskirts of Ranchi, cut off from electricity and other trappings of the modern world, made it seem all the more surreal. Waking up at the crack of dawn to light the kitchen fire, taking rounds of the hospital late at night, even in the biting cold, accompanied by a ward boy swinging his lantern and tapping with his lathi (staff), her days were packed to the last second. At a time when most middle-class households in small-town India ate local, preparing mostly traditional recipes, my grandmother’s kitchen seemed to be a melting pot of cultures and cuisines. Early in the morning, while the household was only stirring into daylight, she would be pulling out unconventional ingredients from the pantry like Chinese spices or Worcestershire sauce to rustle up all three meals of the day that were then kept in ‘meat safes’ or ‘doolies’—wooden cabinets with wire-mesh that stood on stone bowls filled with water to ward off ants and insects.

During her trips to Calcutta, where she had grown up, spiced pork sausages from New Mar-ket were carefully packed, and so was the ubiquitous ‘nona ilish’ (salt-cured hilsa), for the overnight train journey to Muree, followed by a car ride to Kanke. Fruits that were rare in Ran-chi like ‘aansh phal’ or longan—at times called the poor man’s litchi—or date palm or sugarcane jaggery—‘patali’ or ‘jhola gur’, respectively, trundled together to delight friends and family back home. Food at the European Mental Hospital (EMH), shared by doctors and nurses with their counterparts across the fence at the Indian Mental Hospital (IMH), left its indelible mark on my grandmother’s Bengali-Odiya palate, as everything blended in, local and traditional with the exotic and foreign.

During WW II, tinned American bully beef sandwiches, sardines and Nestle chocolates passed around by American soldiers made a startling debut. Interesting additions to the fare were braided pork that Khasi nurses would painstakingly prepare over weeks by braiding, hanging and smoking strips of boneless pork, and elaborate Parsi meals including biryani cooked by Soonabai Umrigar, the no-nonsense Parsi matron at IMH who was grandmother’s close friend. She used to get typically ‘Bombay’ items for her family during her annual visits home—Karachi-Bombay halwa, raspberry drinks, chocolates, apart from issues of Punch, fancy spinning tops, gramophone records and other toys.

It was in her home one afternoon after school that my father heard the wildly popular wartime song ‘Run, Rabbit, Run.’? A Wiki-pe-dia entry says the song was written for Noel Gay’s show The Little Dog Laughed, which opened on October 11, 1939, at a time when most of the major London theatres were closed. It was a popular song during WW II, especially after Flanagan and Allen changed the lyrics to poke fun at the Germans (e.g. Run, Adolf, run, Adolf, run, run, run). The lyrics were used as a defiant dig at the allegedly ineffective Luftwaffe raids over the UK. On November 13, 1939, soon after the outbreak of WW II and just after the song premiered, Germany launched its first air raid on Britain. Two rabbits were suppose-dly killed by a dropped bomb, altho-ugh it is suggested that they were in fact procured from a butchers’ shop and used for publicity purposes. Wal-ter H. Thompson’s TV biography, I Was Churchill’s Bodyguard, rates the song as Winston Churc-h-ill’s favorite as PM.

Winters were the time when the festive season started at the EMH. The entire month of December saw cricket matches, picnics, dinners and dances. It was a time when grandmother, her sister and niece would spend a month preparing cold meat using saltpetre, while chicken, mutton and simple cakes were roasted or baked in an oven over an earthen stove. My father’s maternal grandfather, who settled in Kanke after retiring from Calcu-tta Port Commission, planted an orchard of mango, chikoo and litchi trees so that his grandchildren would not miss out on fruits, and the fertile Chhotanagpur soil yielded a bountiful harvest year after year in its mild summers, when Ranchi—which didn’t have any power supply—didn’t need ceiling fans either.

Cleaning, filling oil, changing the wicks, and lighting a series of lanterns and lamps at sundown were my great grandfather’s routine tasks, and he did so with patience and meticulousness each evening. Around WW II, foreign chocolates, cold cuts, cigarettes and cosmetics such as face creams (or ‘snow’ as they were then called) started trickling into Ranchi’s stores from Calcutta, as did the propensity to add the word ‘American’ to the name of shops. An ‘American Fish Stall’ opened up during wartime, near where Daily Market stands today, offering ready-to-fry fillets of fish, etc., that were not to be found with regular vendors.

Advertisement

My father recounted that his aunt, Ms Pra-t-i-bha Bala Das, a teacher at the Chhotanagpur Girls’ High School, would often stop by at the shop before coming home to Kanke. Since public transport did not exist in the 1930s or 40s, she had a personal rickshaw permanently stationed in the yard, and the rickshaw-puller came every morning to ferry her to school. He would then park his rickshaw, go around the town or take a nap under a tree, and then dutifully bring her back home. The driver of the bus to IMH knew my aunt, my father’s eldest cousin. Any time he chanced upon her on Ranchi’s almost-empty Main Road, he would slam the brakes, shouting, “Chalo Khooki!”, pick her up and bring her to Kanke. Her parents knew if she did not return home from school, she had invariably gone to her ‘other’ home in Kanke.

Advertisement

For dessert, China grass puddings and Rex jelly rubbed shoulders with the usual malpuas, kheer or cake. Ice-cream was prepared by churning milk, sugar and eggs in a hand-cranked wooden ice-cream bucket. It was something that even the old Sanskrit master, who did not usually eat anything outside his own kitc-hen, found hard to resist, asking (though he knew the answer), “This doesn’t have eggs, does it?” The IMH Superintendent at the time, J.E. Dhunjibhoy, took personal inte-rest in all his patients and those who served the hospital. He worked with missionary zeal and was a pioneer, ushering in path-breaking changes in the way mental hospitals were run by introducing occupation therapy, weaving, carpentry, puppetry and other arts for patients. He was instrumental in encouraging my grandmother to undergo further training and polish her skills.

Advertisement

The diet for patients included milk, eggs, butter and fruits. Patients grew vegetables and fruits and had individual gardening patches. For many, it was their best time of the day. Patients visited doctors’ homes, occasionally cooked what they liked to eat or missed.

A few became family. Around the Partition, a patient called Rangta did not want to go home and cried for days staring at the flowerbeds when he was discharged. Grand-mot-her’s was the only home he knew and he had maintained her garden for years. His home was now in a new country, East Pakistan. Emp-athy, like cooking, was natural to her. It was something that her mentor had underscored and written about.

Advertisement

In the annual report of the IMH in 1934, Dhu-njibhoy writes, “In the mental disorder, it is the patient himself who is being treated and not so much other parts of the body, and that is why the personal factor is so important. It is essential to try and see the world as the patient sees it, to accept for the time being the reality of his abnormal experiences and to stand alongside him in his difficulties.”

(This appeared in the print edition as "In Retrospect: Food, Churchill & Kanke")

(Views expressed are personal)

Soumi Das is a Delhi-based teacher and writer originally from Ranchi?

Advertisement

-

Previous Story

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&w=376&dpr=2.0) Post-Polls, J&K Assembly To Pass Resolution For Restoring Special Status And Statehood

Post-Polls, J&K Assembly To Pass Resolution For Restoring Special Status And Statehood - Next Story