Growing up, 41-year-old Sam had never thought that she would become part of a “throuple”, as the Internet these days refers to a relationship between three people. But within the first year of her marriage with her college sweetheart Prashant (name changed), Sam found herself lusting after another person, a common friend. Incidentally, her husband was also attracted to them. “We had always talked about stuff like polyamory or open relationships. But when it happened, it happened very organically,” Sam recalls. “We both fell in love with the same person and they loved both of us back,” she adds.

Married But Open: Indian Couples Embracing Non-Monogamy Say The More The Merrier

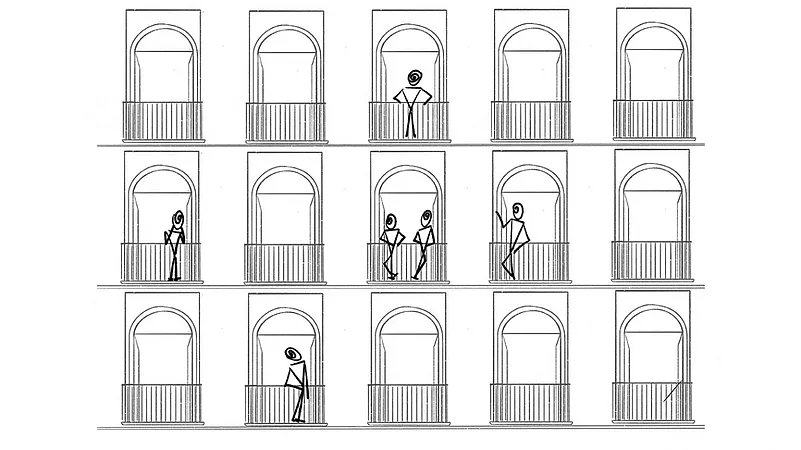

A growing section of 'Non-Monogamous' Indians, especially in urban spaces, are pushing boundaries of heteronormativity in the bedroom and beyond.

Since the first “Ménage à trois”, the duo—who have been together for 15 years and married for seven—have been in an ‘open marriage’. Both have had multiple partners over the years while remaining happy and faithful to each other. “We are more faithful and honest to each other that many monogamous couples that we know,” jokes Sam, who works in a leading newspaper in Kolkata. After all, it’s only cheating if your partner keeps you in the dark, she points out. “And we tell each other everything right down to the hairy details,” says Sam.

The couple has just one ground rule: to never break the marriage. “Even though there is no such thing as the “primary partner” in our dynamic, we know that we have to stick together. We are best friends and we love each other. But we also love other people from time to time,” she states. To understand how they make it work, she stresses that one must first believe in the possibility of being equally in love with two or three different people together. “Each relationship is important in its own capacity and does not diminish the other,” Sam says. Rather, it strengthens it, she adds.

In a society that is generally seen as “restrictive” and closeted when it comes to sex or desires, Sam and Prashant are part of a growing community in India that is openly embracing alternate sexual lifestyles. Going beyond the social mores and gender roles that define heteronormative relationships, these people are pushing the boundary of what’s “normal” when it comes to sex and relationships. Starting with people choosing “love marriages” over “arranged marriages” in the 1960s and 1970s, the ‘sexual revolution’ in post-Independent India has now mushroomed into its most brazen, and perhaps, most tolerant phase yet; a wider—albeit for the most part secretive—movement for greater individual autonomy within familial or intimate institutions hinged on the morality of monogamy.

Learning To Unlearn

The struggles of monogamy are perhaps as old as polyamory itself. Author Ruth Vanita, who has explored queer and atypical relationships and sexuality in India through a historical lens, states that “people of all kinds have always had all types of sexual relationships” throughout history. “Obviously the idea and the practice of polyamory have existed from ancient times. Read love poetry in any language,” she says. Things become more complicated when the concept of “marriage” comes into play. “Polyamory is loving many people, but not necessarily marrying them. Polygamy is a man marrying more than one woman and polyandry is a woman marrying more than one man,” she clarifies.

Both polygamy and polyandry have existed in India, but men have found more acceptance than women. And even in case of men, Vanita points out that there is a degree of disapproval. “Marital morality for most people always included some expectation of fidelity, even for polygamous men,” she adds.

For instance, Vanita points out that a man having a relationship outside marriage with another woman or with a man was often tolerated, so long as it did not interfere with his wife’s or wives’ rights at home and in inheritance. (Many modern day ‘ground rules’ of open marriages are also based on similar principles). A king could have many concubines apart from wives.

“An ordinary man would find it somewhat more difficult. A single or widowed man was freer than a married one. Women often had clandestine relationships, but the danger of pregnancy in pre-contraception societies meant that relationships between women might be safer,” she adds.

While certain sections of women (such as Sam) today have more control over their own bodies and sexualities than in the past, a majority of Indian women still find it taboo to talk about their needs with their respective partners. A case in point is that of 36-year-old school teacher Varsha (name changed) from Delhi’s Vasant Vihar who states that she approached her husband of three years with the idea of trying an open relationship after she caught him cheating. “He is a good man and I did not want to break the relationship. But when I confronted him, he freaked out at the thought of me having other sexual partners,” she says. At present, she remains married to her husband (who has since apologised for his ‘slip up’) and both have been trying to remain “faithful” to each other. Varsha feels that it’s only a matter of time before one of them cheats again.

On the other hand, Kanpur-based businessman Anup Bansal (name changed) says that after 12 years of marriage and one kid, sex between him and his wife had fizzled out. “It’s not that we didn’t enjoy each other’s company but after a point, it became impossible to maintain an active sex life,” he says, adding that he often felt ashamed in trying out new things in bed with his wife, whom he had started seeing as the “mother of his son”.

“The situation became unbearable in 2020 during the Covid-19 lockdown when we were forced to stay with each other 24X7. That’s when we talked and decided to try out ‘open marriage’ experiment,” says Anup. So far, it has worked. “We have managed to maintain our boundaries and respect for each other while also exploring our own sexual desires,” he says, adding that either person can ask the other to get out of any arrangement that they were not comfortable with. He admits that keeping jealousy at bay has been a challenge for both, especially him. “There’s a lot of unlearning, especially when it comes to my wife. Women are conditioned to believe in these notions of purity while men are taught that women are their sole property,” says Anup.

While still a taboo in most households, a number of couples in India today claim that non-monogamy has helped renew their relationship with their primary partner and bring back the effervescent “spark”. “As a form of relationship therapy, open marriage may potentially work for certain couples by introducing novelty, fostering increased communication, and exploring new aspects of their partnership. It allows them to confront issues like trust, insecurity, and communication head-on,” says relationship counsellor and mental health professional Shivani Misri Sadhoo.

However, Sadhoo warns that it isn’t suitable for everyone. “Certain individuals could find that monogamy aligns better with their values and emotional needs. Every single relationship is unique, and what works for one couple may not work for another,” she adds. “It is essential to remember that Indian society, including urban India, is still predominantly rooted in traditional values, which might continue to influence the majority of couples’ preferences for monogamous relationships,” says the therapist. Open marriages might still be perceived as unconventional and face social stigma or disapproval, leading many couples to opt for more traditional relationship structures.

Social acceptance of alternate forms of relationships needs to be preceded by legal acceptance. The fact that many like Sam and Anup today have ventured beyond the traditional confines of binary, monogamous and heteronormative relationships in India, perhaps reflects to some measure the success of several progressive court verdicts and changes in legal frameworks or laws surrounding relationships, gender and sexuality.

Be it the decriminalisation of adultery which previously allowed men to prosecute the “extramarital lovers” of their wives (without allowing women to do the same), or the decriminalisation of Section 377 which prohibited sex between men, or bestowing legal rights to women in live-in relationships, the courts in India have helped forge the backbone for growing acceptance of alternate romantic lifestyles and marital choices. In 2022, for instance, the Supreme Court acceded that familial relationships may take the form of domestic, unmarried partnerships or queer relationship and that same-sex couples and other non-traditional families, like unmarried partnerships and single parents, are entitled to legal protection and social benefits.

Despite these progressive changes, however, the shift in mentalities and attitudes of people at large has been slow, especially for gender or sexual minorities including women and the LGBTQIA community. The challenges are doubled in cases of intersecting marginalisation of gender, caste, class and religion.

Balancing Act

For the most part, both mental health and relationship experts as well as practitioners of non-monogamy state that the key to a successful open relationship is consent, honesty, and emotional well-being of all parties involved. There are challenges, of course. Keeping multiple partners engaged while also finding time for self-care and growth can be tricky and dealing with feelings of jealousy and inadequacy that are bound to creep in can amount to quite a bit of mental gymnastics.

“Just like any other relationship, jealousy and insecurity naturally seep in. We are human after all,” says polyamorous artist Soumyadeep Roy. “But it’s only how you continue to fight it within is what matters. Of course, transparency and clear communication with your partners is crucial,” he adds. For some like Sam, jealousy is indeed a virtue. “Any relationship thrives on a bit of jealousy, a bit of possessiveness. It prevents us from taking our partner for granted. If there’s a third person in the picture, it’s but natural for one to try harder to hold on to their partner’s affections. It helps us love each other better,” she states.

But what if the idea of marriage itself is brought to question? Roy, for instance, feels that for non-monogamous people, marriage as an institution can be too patriarchal restrictive. “It helps with legalities, to get a house together, etc. But to get the government involved into something so personal as a relationship sounds ridiculous,” he says. The artist claims that in an ideal world, he would be sharing his house with someone he’s compatible with, not necessarily sexually or romantically attracted to, but even like a friend or a sibling, and that could be his family. It could be with multiple people too. “I always felt that one can be romantically attracted to someone and sexually attracted to someone else and platonically attracted to someone else altogether,” he says. All these could be with different people and could lead to unique relationships, just as people are unique in themselves.

(This appeared in the print as 'Open Secret')

- Previous Story

Marital Rape 'A Social Issue Not Legal', Centre Files Affidavit With SC Against Criminalisation

Marital Rape 'A Social Issue Not Legal', Centre Files Affidavit With SC Against Criminalisation - Next Story