The news of Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal’s arrest by the Enforcement Directorate (ED) nearly two months ago on March 21 left many in Delhi upset, including 33-year-old Sonu Kumar, a shop owner. A resident of Sunder Nagri in northeast Delhi—Kejriwal’s karambhoomi where he began his anti-corruption movement over three decades ago—Kumar states that everyone in the locality knows Kejriwal. “He used to work in a small office nearby from where he ran his campaign, Parivartan,” Kumar recalls. As a teen, Kumar used to regularly visit the Ramlila Maidan in 2011-12 during the Lokpal movement. “I used to go to hear his speeches. Everyone in our neighbourhood joined the protests. We wore Anna caps (named after anti-corruption activist Anna Hazare) and joined the agitation. We all believed in him,” he recalls. Over the years, he watched Kejriwal continue his fight against corruption from the streets. In 2013, Kejriwal sat on a hunger fast for two weeks against exorbitant electric and water tariffs. It was here that the movement started taking a political shape in the form of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP). “It happened in this very neighbourhood,” says Kumar. “He is such a simple man, always dresses and speaks humbly like all of us. I can’t believe they are accusing him of corruption now,” Kumar says with a sigh.

Trapped: With Arvind Kejriwal's Arrest, What Is The Future Of AAP?

It is time for Arvind Kejriwal to do some soul-searching

The arrest of Kejriwal, a sitting chief minister and opposition leader ahead of the Lok Sabha elections 2024 in April, raised an alarm and several questions about the fate of democracy in the country. Although the Supreme Court on Friday granted Kejriwal interim bail until June 1 and asked him to surrender the next day, for many like Kumar, the arrest also raised other important questions—what happened to AAP? What happened to Kejriwal? The fastest-growing political party in the country in the last decade, once dubbed the herald of political change, is now being accused of corruption, the very demon it was created to fight.

The fastest-growing political party in the country in the last decade, once dubbed the herald of political change, is now being accused of corruption, the very demon it was created to fight.

Post-Ideology Politics

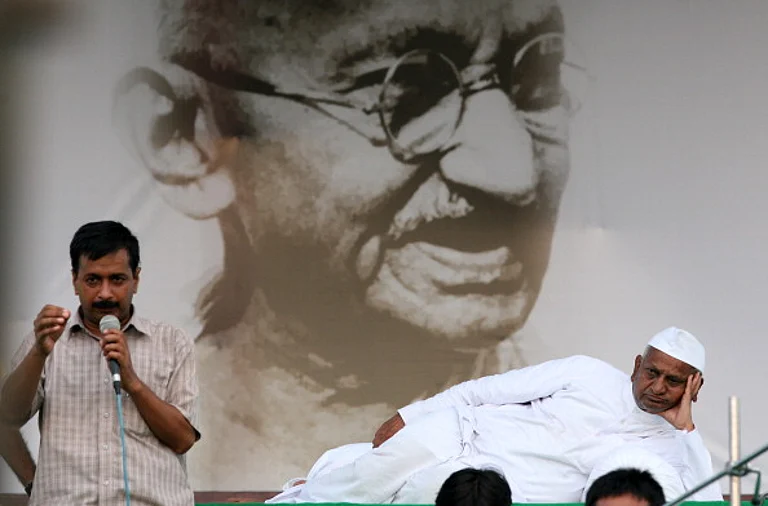

It all began in 2011 when Hazare sat on a hunger strike against the then Congress government which was mired in multiple scandals. The aim of the movement was to fight for clean governance and remove corruption from high places. By the time the India Against Corruption movement strengthened, Kejriwal was already a known face among activist circles. He had been conferred the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 2006 for his role in the Parivartan movement, which channelised the Right to Information legislation as part of a campaign against government corruption. He had also founded the civil society organisation called Public Cause Research Foundation, which worked towards increasing transparency in governance. He had also worked as a tax investigator in the Indian Revenue Service, a job he left to pursue activism full time. It was the 2011 protest, however, that propelled him to national attention.

“The massive success of the Anna Hazare movement created an all-India ecosystem in which ‘anti-corruption’ became a buzzword. Because the movement generated so much goodwill, its leadership was advised to convert the movement into a party in order to get sustained and maximised results on the ground,” says Ashutosh, a former founding member of AAP. Kejriwal emerged as the political face of that movement. As a political outsider, an IIT-ian who had already cut his teeth in socialist street protests, Kejriwal clad in a simple sweater and muffler and armed with his suburban mannerisms was perfect as the champion of the ‘Aam Aadmi’ (common man). While Hazare provided the movement with its Gandhian moral underpinnings, Kejriwal was its soldier on the ground.

The AAP was the product of a movement, led largely by non-political, civil society actors. Unlike ideologically strong parties—like the BJP, which is based on religious majoritarianism, or the CPI(M), which is based on Communism—the AAP did not start with an ideology. Instead, it promoted its functionality (anti-corruption) as its core value. It de facto espoused features of what political scientists refer to as a “post-ideological system”.

“The idea of the AAP was to operationalise post-ideology politics. Ideology can be narrow. Instead, the party shifted the focus to service delivery in order to get mass appeal. There were poor people who needed certain services and the state could provide it using its resources,” says sociologist S S Jodhka. The party emerged as part of a wider global process, with neo-liberal economic systems becoming the standard.

The idea of welfare for AAP was more ‘freebie-oriented” where cash or benefits were doled out to those in need. Instead of addressing institutional inequalities, it simply focused on improving access.

The intrinsic difference between an ideological party and a party based on service delivery is that the former usually engages in transformative politics. Such systems emerged in the post-Second World War period, when many new countries emerged with backward economies and traditional social orders. From a Leftist angle, these were feudal or semi-capitalist societies that needed to be transformed into progressive cultures. In India, the Congress, which remains largely a party without a common ideology, also took on a transformative role, be it through land reforms, or through its emphasis on campaigns like the Right to Food. While the Congress, in its early years, acted like a welfare state, taking centralised and moral responsibility for improving infrastructural metrics, the idea of welfare for AAP was more ‘freebie-oriented’ where cash or benefits were doled out to those in need. Instead of addressing institutional inequalities, it simply focused on improving access. While the AAP has managed to improve Delhi’s health and education infrastructure, in keeping with its service delivery approach, the act of service delivery itself was not enough to mobilise cadres. “The AAP, unlike the Congress, has not been able to make its foray into transformative politics. The absence of a strong ideology and participation in transformative politics is one of the reasons it is failing to mobilise cadres on the ground today,” notes Jodhka.

Moreover, the Congress also makes up for its lack of ideology with its historical legacy of anti-colonialism and the freedom movement. It has been blessed with colossal leaders in the past. The AAP remains missing from such “institutional memory” and in recent years, the party’s credibility has taken a beating. A series of allegations, including the excise liquor policy case, a money laundering case involving the Delhi Jal Board, and controversies like the row over Kejriwal’s alleged Rs 40 crore home renovation project using public funds, have led to questions among voters regarding the party’s “clean” image.

“Kejriwal must realise the mistake of the AAP in alienating the intelligentsia from the party. It was people like Yogendra Yadav, Prashant Bhushan, Ashish Khetan, Ashutosh and other civil society members who brought credibility to the party,” says political scientist Manindra N Thakur.

The first term after 2013 was relatively idealistic and much of the AAP’s good work was done in that period. “When I joined the AAP, it was a party of hope. Everyone had a lot of dreams. We all thought that this party would change the country, the political structure, and the system. And that this party is part of history-making. But over time, politics appropriated the AAP and it started behaving like any other party,” states Ashutosh.

It was only after the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, when the party lost all seven seats in Delhi, that the top leadership realised that to keep the movement alive, the party had to stay in power. “The party began to flout its own rules of transparency and filtering when it came to selection of members and candidates,” a former AAP leader states. Initially, members joining the AAP had to undergo a six-month-long period of ground work without any post or ticket. There was also a strict selection criterion for members, and people with past allegations of corruption or ideological differences were not given preference. These rules were soon ignored by the top leadership, leading to questions among the party’s leaders and founding members. In 2015, the party expelled senior AAP leaders such as Bhushan, Yadav, Anand Kumar and Ajit Jha for “anti-party activities”.

In 2018, the party ignored senior leader Kumar Vishwas, and instead, nominated veritable outsiders such as Sushil Gupta and N D Gupta, alias the ‘Gupta brothers,’ for Rajya Sabha berths. Ashutosh, who quit the party in 2018, recalls that there was a culture of meetings and consultations initially, which seems to have disappeared over time. “Now one man’s dictum is the rule. The voice of dissent has almost disappeared. The democratic process of consultation has also disappeared,” he says. While calling Kejriwal a “gifted” man and commending his one-track dedication to his goal, Ashutosh adds that the party’s weakness lies in its failure to create an organisational base.

Congress leader Alka Lamba, who earlier had a stint with the AAP, says that the AAP has failed to live up to its other promises like anti-nepotism. The former AAP MLA from Chandni Chowk cited examples of former Congress leader Mahabal Mishra, who is fighting the Lok Sabha election on an AAP ticket from West Delhi, where his son Vinay Mishra is the MLA (Dwarka). In Matia Mahal, ex-Congressman Shoaib Iqbal is the AAP MLA, while his son, Aaley Mohammad Iqbal, is the deputy mayor of Delhi. “Incidentally, this is the same man that Kejriwal had previously called corrupt in 2015,” Lamba adds. In Chandni Chowk, Parlad Singh Sawhney is the MLA, while his son is a councillor.

During a hunger strike in his early days, Kejriwal had expressed his concerns over becoming corrupt if he came to power. While Kejriwal’s innocence or guilt is yet to be proven, the arrest seems to be a reminder of his prophecy.

Ideology vs Opportunism

Critics have also pointed out that over the years, Kejriwal’s secular and inclusive politics have taken a majoritarian turn. “In its initial years, the AAP championed minorities like Muslims, Dalits and the Other Backward Classes (OBCs), which have traditionally voted against the BJP. But after the 2015 elections, the party started to take its minority vote bank for granted,” a former AAP leader states.

The party further alienated Muslim voters and harmed its ‘secular credentials’ with its strong stand against the Citizen (Amendment) Act, 2019, protests and its failure to deal with the 2020 northeast Delhi violence. The fact that the party understands this is reflected in its seat-sharing deal with the Congress ahead of polls this year, in which the Congress is contesting from Muslim-dominated seats like Chandni Chowk and Northeast Delhi.

“The advantage of not having an ideology is that it allows for political opportunism,” says Jodhka. In recent years, Kejriwal has been making overtures to what has been dubbed as “soft Hindutva”. While the party has not espoused Hindutva politics overtly, it has been increasingly trying to attract the Hindu upper caste, upper class voters in Delhi through pujas, satsangs, Hanuman Chalisa recitations and more. In 2022, Kejriwal sparked criticism after he suggested that images of Hindu deities Laxmi and Ganesh should be printed on currency notes. In 2021, his government launched the Mukhyamantri Tirth Yatra Yojana, under which senior citizens of Delhi were given the facility to visit any of 12 listed pilgrimage destinations free of cost. The first batch of tirth yatris visited Ayodhya in 2021, even before the consecration of the Ram Mandir in 2024. Jawaharlal Nehru University researcher Prateek Vijayavargia, who is writing a thesis on the AAP’s politics of movement, feels that the religious symbolism of the AAP is not new. “Even during the inception of the Anna Hazare movement, political observers had noted the presence of a large number of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) cadres as well as the use of Hindu symbolism and messaging. Yoga guru and businessman Baba Ramdev also managed to hijack the movement in parts. For many, the purpose of the movement was to destabilise the Congress in New Delhi, rather than working towards igniting any real political consciousness or change,” Vijayavargia feels.

While Ashutosh states that “the Kejriwal he knew” was not an overtly Hindu man, he believes that the AAP chief can profess to be so if he feels it would help him get votes from a certain community. A former AAP leader, on condition of anonymity, states that such “duality” is not uncommon for Kejriwal. “He has two personalities: one that he tries to project—as this anti-establishment crusader—and the other, which is driven by power. He started out as an activist, but later fell into his own trap,” says the former AAP MLA. During a hunger strike in his early days, Kejriwal had expressed his concerns over becoming corrupt if he came to power. While Kejriwal’s innocence or guilt is yet to be proven, the arrest seems to be a reminder of his prophecy. Meanwhile, the party’s future will depend on which road it takes between functionality and ideology.

- Previous Story

Marital Rape 'A Social Issue Not Legal', Centre Files Affidavit With SC Against Criminalisation

Marital Rape 'A Social Issue Not Legal', Centre Files Affidavit With SC Against Criminalisation - Next Story