Bandit King

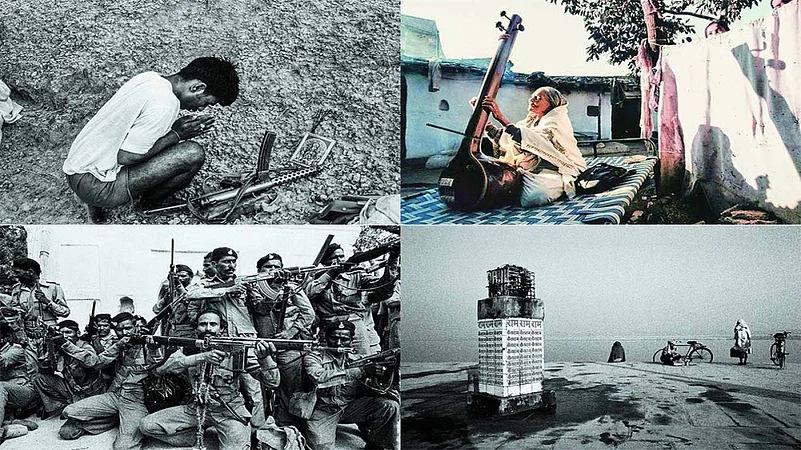

Freeze Frames: A Wanted Dacoit, A Fading Dhrupad Legend And Smouldering Ayodhya

The stories behind some of the most iconic photographs by Prashant Panjiar.

By late 1981, Brij Raj Singh, a recent history graduate from Delhi University, joined Kalyan Mukherjee and me to work as a researcher on our Chambal book project. Even while we spent time in the field researching the history of banditry, we continued our efforts to contact Malkhan Singh.

But getting to Malkhan was not easy. We spent months chasing him, sending messages through his support system in his sanctuary, Bah Tehsil in Uttar Pradesh’s Agra district. But he refused to make contact. Our first two intermediaries failed and the third, retired Army Subedar Viren Singh Bhadoria was arr-ested in January 1982 under the new Anti-Dacoity ordinance. When we met the Subedar in jail, he told us that Malkhan was contemplating surrender and if we got him out, he could take us to him. That started a long, secretive negotiation process bet-ween us and the then Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh Arjun Singh, spearheaded by Kalyan. It took us three months to secure the release of the Subedar and finally in May 1982, in the dead of a dark night, we met Malkhan for the first time. Even though we were instrumental in the negotiations, it was only in the final days leading up to his surrender in June 1982 that Malkhan gave us any real access to his gang. Kalyan and Brij would go in and out to talk with officials and make arrangements for the surrender, but I got to spend a few days with the gang. I was happy to be “hostage”, their guarantee against betrayal, as long as I was getting my pictures. A fair deal, wouldn’t you say?

Our book changed and became Malkhan: The Story of a Bandit King, which was finally published in 1985. It is amazing how, despite the fact that the book has been out of print forever, it continues to have a life of its own, becoming a super-important resource on the Chambal dacoits. As for me, my work on the book helped launch my career in photojournalism and for that I will remain eternally grateful to my compatriots, Kalyan and Brij, who sadly are no more.

Dhrupad Diva

In late 1996, Outlook correspondent Soma Wadhwa and I travelled to Tikamgarh in Madhya Pradesh to meet the legendary 86-year-old Dhrupad singer Asghari Bai. She had just then ann-ounced that she was returning her prestigious government honour, the Padma Shri, because she was living in penury and receiving no support from the government.

Asghari’s mother, a servant of the Nawab of Tonk, was gifted to a courtesan and ended up as a court singer. Asghari would have met the same fate had it not been for Ustad Zahur Khan from Gohad, who took her in and schooled her in the art of Dhrupad. She was at the peak of her career from 1981 onwards, performing at concerts in India and abroad. But unlike other performers who also sang the more popular Ghazal and Thumri, Asghari was not able to leverage her fame because she insisted on singing only pure Dhrupad. Though receiving the Padma Shri was a great honour, it also bec-ame a liability. Those who would earlier invite her to sing at small functions in their homes stopped, as they felt foolish paying her the usual small fees she till then had supported her family with.

We found Asghari Bai sitting on a bed in the courtyard of her modest home. Bitter and angry, she told Soma: “I want the Sarkar to take back my Padma Shri! I’ll barter it for two square meals a day. I’ve discovered my family can’t lick it when they’re starving!” She narrated her woes and told Soma about her turbulent history while I circled around her, making my photos. But Asghari Bai was also playing to the gallery. So while there were tears and rants, there was also humour, mischief and plenty of coquettishness. She was performing for the camera and when I asked if she would sing for us, she obliged. I was in heaven hearing her raspy melodious voice and spent quite a bit of time making photos from all possible angles. And she was enjoying every minute of the attention she was getting from me. Before we took her leave, Asghari Bai called Soma aside and referring to me, said, “Isko rakh lo. Achchha hai!” (Make him your keep. He is good!). What better compliment could one hope to get from a woman?

Eye Of The Storm

I was in Ayodhya on December 6, 1992 when the Babri Masjid was torn down. But I had not been back since. So for the 10th anniversary I convinced Sunday Express, which I had helped launch a few months earlier, to send me to Ayodhya. The year 2002 had been a whirlwind one for me—I had spent 252 days on the road, rushing from one story to the next. But for Ayodhya, I was determined to take it slow. So I arrived in advance of the writer Sankarshan Thakur and spent the next few days wandering around the town trying to discover what this place was about.

The violence and communal divisions caused by the Ayodhya dispute have defined the contemporary soc-ial and political history of our country. Consequently, the town had come to be imagined as dark and dangerous, a place to be avoided. In reality, Ayodhya felt more like it was asleep, in decay, crumbling, ignored and forgotten, even while being bound by all kinds of barricades. The number of pilgrims visiting had dwindled. There was a feeling of res-igned acceptance amongst the residents. Nails were driven in the walls to keep the monkeys away, but they did not. The traditional salutation of ‘Sitaram’, was giving way to just ‘Ram’ on a pillar on the bank of the Saryu river. The faithful read the Hanuman Chalisa in books and on the walls of the principal temple, Hanumangarhi. And young boys showed me the infla-mmatory pamphlets that they were hawking to the few pilgrims returning from the makeshift Ram Janma--bhoomi temple, while a family of monkeys watched their antics. These photos bec-ame the starting point of a long-term engagement with Ayodhya for me to work on a book with the working title Eye of the Storm.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Camera Lucida, Or How The Subject Shows Up")