Let us assume that Savarkar was not an accused in the Gandhi murder case. He would have lived in relative obscurity—as the Hindu Mahasabha, of which he was the leader, was never a force to reckon with. Maybe, at the 100th anniversary of 1857 he would have been given prominence as an early historian of that event. The Congress and the left would not have made much of his petitions to the British and he would certainly not have been reviled as he is today. In fact, he would have been hailed not only as a patriot who spent years in Andaman’s Cellular Jail but as a pioneer of anti-caste movement. The Gandhi murder changed all that. Was he really involved in the murder?

Untold Stories From Veer Savarkar’s Life And Times

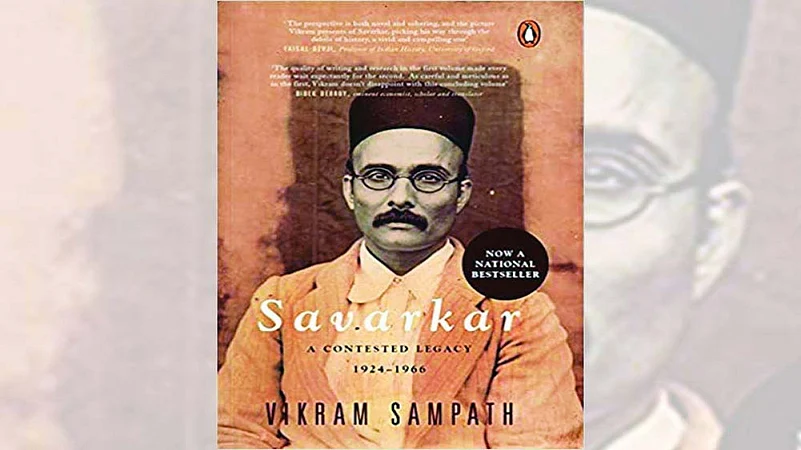

In this concluding volume of his sympathetic biography of the RSS icon, Vikram Sampath focuses on the Hindu Mahasabha’s role in the freedom movement and the Gandhi murder trial.

Vikram Sampath, in his meticulously researched book, establishes that the police case was amateurish and unprofessional. Yes, both Godse and his friends visited his house in Mumbai but there was no credible evidence that they discussed the murder plan. Savarkar, says Sampath, just ignored Godse and others during the trial, treating their overtures with cold contempt. Yet, the answer to the question is still not available.

Between 1924 and 1937, Savarkar was largely confined to Ratnagiri district, thanks to the government’s restrictive orders. During these years, he met the Hindu orthodoxy head on. He encouraged inter-dining and said, “The abolition of the caste system is far more important than the mere thinking of political movements”. However, he held that responsibility for the abolition of untouchability and the division created by the caste system lies not only on the shoulders of the upper castes. One can say that the rigours of the caste system have been broken, he argued, only if it can be proven that Mahars share food not only with Brahmins and Marathas but with Bhangis too. He was contemptuous of the varna system and said that when a fifth varna of untouchables was created, the four-varna system had been destroyed.

In 1937, he was appointed president of the Hindu Mahasabha. In his inaugural speech he proclaimed that India could not be considered a homogenous nation, that there were two nations—“Hindus and Muslims”. While he envisaged a Hindu Rashtra which would not recognise distinctions on the grounds of religion and race, he chided Muslims for ignoring the nati-onal struggle, but reappearing at the time of reaping its fruits. He also accused them of harbouring extra-territorial allegiance. As Sampath points out, it was such excessive codification and formulaic definition that contributed in preventing several sections from accepting the Mahasabha’s viewpoint. Whatever little support the party had evaporated when it decided not to participate in the Quit India movement. The Mahasabha, in fact, formed a coalition with the Muslim League in Sind, NWFP and Bengal when Congress leaders were in jail.

After his acquittal in the Gandhi murder case, Savarkar led a life of unrelieved misery. He could be extremely petty-minded and treated his wife and loyal assistant very shabbily. He became a recluse, refusing to meet even Field Marshal Cariappa. Surprisingly, he gave a remarkable interview in 1965, in which he spoke of the India of his dreams—an ‘akhand Hindustan’ with a secular government formed on democratic principles and a casteless Hindu society. All land would belong to the state eventually and all key industries would be nationalised. He says his mantra would be to “Hinduise politics and militarise the nation”, but claimed he was not a Hindu communal fanatic.

Whatever Gandhi was, Savarkar was not. But that could not have been the reason why our historians have consistently ignored him. Sampath deserves our congratulations mainly because he has succeeded in disturbing this silence. His is a sympathetic biography; I am sure others will now write critical ones, enriching our understanding of the freedom movement and possibly its most controversial personality.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Man In Dark Shades")