In late 1907, Britain’s foremost war correspondent, Henry W. Nevinson, arrived in India to report on the growing Indian nationalist movement. In the south, he saw “a simple factory among the palms of the north of Madras”, which ventured to manufacture Swadeshi handlooms, following the lead of the extreme nationalists. The ‘wealthy Hindu’ who ran this factory was Pitti Theagaraya Chetty (1852-1925), the same man who the Congress would dub as ‘anti-national’ less than a decade later, for issuing the Non-Brahmin Manifesto.

Footprints Of The Original ‘Anti-Nationals’

The Non-Brahmin Manifesto attacked injustice; the Justice Party sought a remedy by the earliest adoption of reservation and secularisation by law.

Anti-national was not the only abuse hurled at him. His party, the South Indian Liberal Federation, was later called the Justice Party after its flagship newspaper was debunked as collaborationist, serving British colonial interests for the fishes and loaves of office. But Theagaraya Chetty would turn down the chief ministership of the Madras Presidency when his party swept the 1920 elections. So much for being collaborationist and anti-national. Calling one’s political opponents anti-national is apparently no new weapon.

In this movement of so-called anti-nationalists and collaborationists, Theagaraya Chetty was joined by Dr T.M. Nair (1868-1919), an Edinburgh-trained doctor. Associated with the grand old man of Indian nationalism, Dadabhai Naoroji, during his London days, Nair was a regular at the annual gatherings of the Indian National Congress. But when these two nationalists, Nair and Chetty, their accomplishments and commitment to the national cause notwithstanding, realised that they were being side-lined by the behind-the-screen machinations of a Brahmin-dominated Congress, they launched a new organisation.

And when the British, who looked at educated Brahmins with suspicion, provided through a series of administrative enquiries, the figures and numbers that demonstrated the fact of Brahmin domination in every sphere of public life—education, the professions and official positions—it only confirmed their lived experience. As the nationalist movement gat-hered force, with a demand for some form of Home Rule, the non-Brahmin leaders wondered what might be in store for them in a free India.

These fears were articulated in the Non-Brahmin Manifesto, issued at the historic meeting in the Victoria Public Hall on November 20, 1916. The manifesto, articulated in a language that would do credit to any liberal intellectual, pointed out that though “Not less than 40 out of the 41 1/2 millions” of the Madras Presidency were non-Brahmins, “in what passes for the politics in Madras they have not taken the part to which they are entitled”. Arguing that a government conducted on “true British principles of justice and equality of opportunity” was in the best interests of India, it declared, in words reminiscent of the early Congress, that “we are deeply devoted and loyally attached to British rule”.

The Justice party won the first elections under the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms. Within the limits of dyarchy—the political arrangement under which the bulk of powers remained with the executive and only ‘the transferred subjects’ were handled by elected (by a limited franchise) ministers—the Justice ministry had many landmark achievements to its credit.

|

| ||||

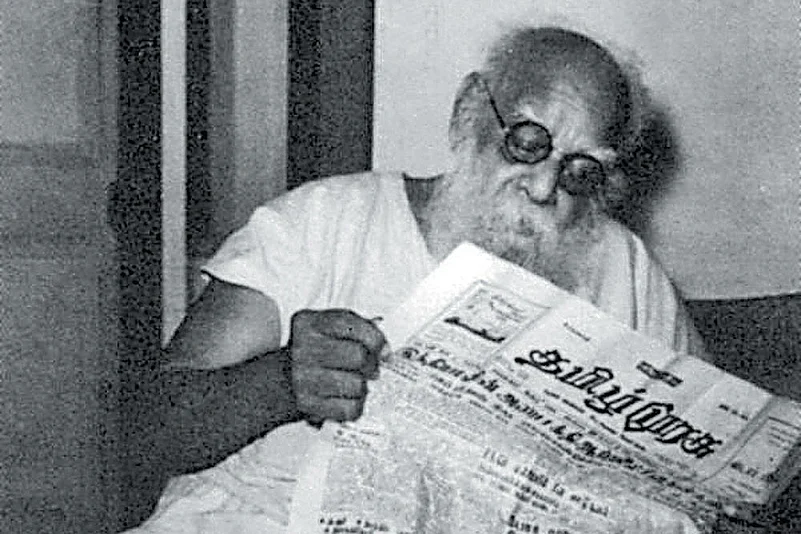

T.M. Nair | ? | Theagaraya Chetty? | ? | N. Mudaliar |

The so-called ‘communal government orders’ of 1921-22 introduced reservation on the basis of caste, and opened new avenues for backward caste mobility. Starting from government jobs, reservation soon enc-ompassed education. This form of positive discrimination became the model for the rest of India, manifesting itself in the Mandal Commission recommendations a good seven decades later. The first amendment to the Constitution of India that sec-ured reservation in the face of an adverse Madras High Court verdict (Shenbagam Dorairajan vs Union of India) was the result of an agitation centred in Tamil Nadu. Even as North India continues to grapple with the mechanics of reservation, it works with clockwork precision in the south. The profile of the South India’s higher education must warm the heart of every champion of social diversity. The fruits of reservation enjoyed by backward castes across India is in no small measure due to the demand articulated in the Victoria Public Hall during a monsoon evening a hundred years ago.

The Hindu Religious Endowments Act, 1925, at once stroke kick-started the secularisation of Tamil society. The numerous well-endowed temples, marred by maladministration and reeling under the control of locally dominant castes, now came under the state. That ninety years later Hindutva forces continue to clamour for its abolition speaks for the foresight of this legislation.

Why are these far-reaching moves of such great import so little known outside of Tamil Nadu?

T.M. Nair’s premature death, in 1919, in London, and Theagaraya Chetty’s death in old age, in 1925, at a historic juncture deprived the party of a sagacious leadership. But this loss, was also an opportunity. The non-Brahmin movement took a vernacular turn with the rise of E.V. Ramaswamy Naicker, later to be venerated as ‘Periyar’. In an age of democratic politics, from the late 1920s, Periyar shaped the Self-Respect movement and took it to the streets. This had the effect of sidelining the English-speaking non-Brahmin elite—much as Gandhi had done for Indian nationalism. It was this elite that M.N. Roy tried to tap into when he spearheaded the Radical Democratic Party in the 1940s. However, he soon forsook the likes of S. Muthiah Mudaliar, ‘Sunday Observer’ Balasubramaniam and T.A.V. Nathan, all Justice Party stalwarts, and tried to forge an alliance with Periyar.

The vernacular turn meant the loss of advocates who could articulate the non-Brahmin movement’s programmes and defend it against the calumnies heaped on it. Not until the rise of area studies scholarship from the American universities did reasoned accounts arguing the non-Brahmin movement’s case reach outside audiences.

The Justice party functioned within the colonial pub--lic sphere, using the language of liberalism and con-stitutionalism. Periyar rejected that idiom and cha-llenged the roots of inequality by attacking caste, religion, and patriarchy. This campaign led to a direct confrontation with a socially retrograde nationalism which compromised with feudal values. One of the high points was the anti-Hindi agitation (1938-39), launched against the compulsory study of Hindi in schools. Periyar’s movements in the 1950s—the breaking of Hindu idols, the burning of the images of Ram, and the torching of pictures of Gandhi, the Constitution and the national flag—chipped away at the monolithic conception of a nation based on a single language, a single religion, and an upper caste leadership.

Periyar eschewed electoral politics, preferring to play the role of unhidden persuader. Yet his impact on Tamil politics continues to remain palpable. A breakaway group, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, led by his protege C.N. Annadurai, pulled the carpet from under the Congress and scripted the political empowerment of backward castes. And, consequently, one or the other Dravidian party has ruled Tamil Nadu for a half a century now. On the other hand, Periyar’s movement also triggered the debrahminisation of the Congress, and his support bolstered the chief-ministership of K. Kamaraj.

Though the English-speaking elite remained ignorant of Periyar’s radical programmes, his imprint is discernible in backward castes movements across India. His leadership of the Vaikom Satyagraha in 1924, won him the support of the Ezhavas of Kerala. And their leaders such as Sahodaran Ayyappan rem-ained in conversation with him all through his life.

Periyar’s initial recognition of Dr Ambedkar as the sole spokesperson of India’s Dalits strengthened his hands, even as he was cornered from all sides. Not surprisingly, the history of the Dalit movement in Tamil Nadu is intertwined with Periyar. Periyar’s north Indian tours in the 1950s and 1960s kindled the hopes of backward castes. It was therefore appropriate that Kanshi Ram should invoke his name when he mobilised the Bahujan Samaj in the late 1980s.

At a time when Hindutva forces are riding the high horse of nationalism, the ‘anti-nationalism’ of Periyar and the non-Brahmin manifesto deserves to be commemorated, and not only in Tamil Nadu.

(The writer is presently working on a biography of Periyar)