The Soil Beckons

The years in other cities have only strengthened my sense of belonging to my roots in Assam

Homeward Bound: Bharalumukh against the backdrop of the Nilachal Hills

My native place, for me, is a series of images haphazardly placed, but evoking the same sentiments each time I play them through my mind. I rewind, pause and fast forward as I wish, and my mind takes me to and fro faster than I wish.

Memories of Guwahati are inextricably linked with my maternal grandfather, Gaurisankar Bhattacharya, and his rugged and austere approach to life. A devout Communist and intellectual, he was, in his time, Guwahati’s most celebrated jurist. His library had a smell of its own. It was dark and lined with the most eclectic range of books that I had ever seen—from legal tomes and all the publications of the People’s Publishing House to American paperbacks and the best of Herge. "This boy has to be exposed to the Assamese outdoors," he would tell my mother, as he put on his gumboots to take me in his 1967 black Ambassador on a fishing expedition to his farm and pond in the heart of Guwahati. He would lay the nets himself, go into the muddy water, and hold up for me the biggest rohu he had caught. After that he would laughingly pull the leeches off his legs. I once dared to ask him, "Why do you do all this—go into the mud, and let the leeches crawl on your leg, when you can buy all the fish you want?"

He looked reflective for a moment, and then answered, "So that I don’t forget my roots." Those immortal words have said stayed with me to this day.

If I calculate hard, it strikes me now that I have not spent more than fifteen per cent of my living days in Assam. And yet, it seems even more my native place today than it did when I was in school or college. In a strange and inexplicable way, I find myself identifying more with local issues and concerns than I did earlier. Is it because I want to deny the rootlessness of the years spent between fifteen different cities in India and abroad? Frankly, I don’t know. But as I grow older, my own definition of my native place has also begun to expand.

I remember the year I spent living in a 200 sq ft room on a terrace in Calcutta’s Keyatala Lane. I was straight out of Oxford, starting my career as a journalist with The Telegraph, didn’t speak a word of Bengali, and lived a carefree life between Haldirams, Flurys, Blue Fox, the then brand new Metro, the always smoke-filled edit department, the cheap pirated cassette shops on Freeschool Street and the Allahabad Bank branch near Park Street, where I felt loaded every time I withdrew Rs 200 after standing in a sweaty line for half an hour. It’s the shortest career stint I had, and in less than a year I had left to be a TV journalist in Delhi. But in that very short period, I developed an affection and a bond with Calcutta so strong that I found it difficult to explain to myself. Where else would you have a conversation on a book you were carrying with an absolute stranger on a bus, find a colleague desperately writing poetry in an oven of a room on a summer afternoon, and establish a strange rapport with the owner of the Ganguram sweet shop in Gol Park that went beyond the free ‘shingaras’?

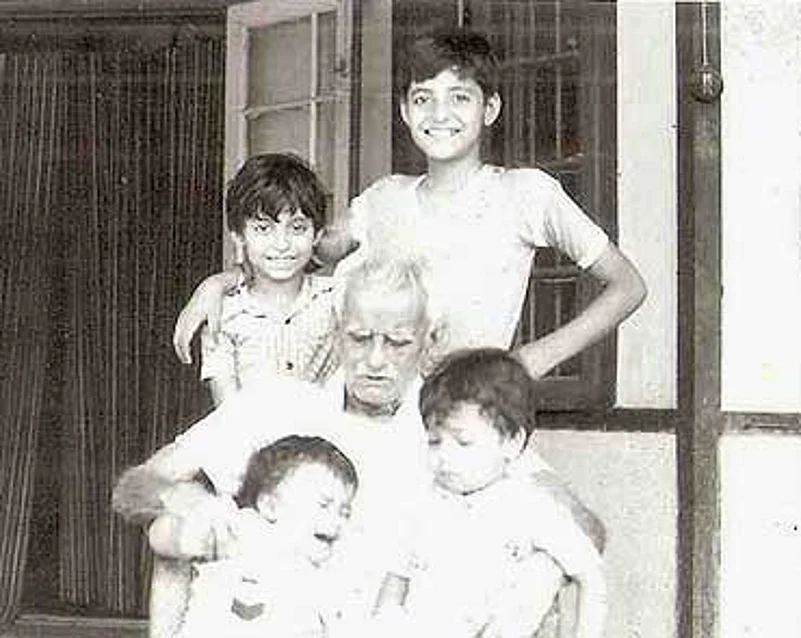

Arnab, standing right, with his grandfather

And so, in my own mind, my roots began to spread, linking me to Calcutta as well. One obvious link was to Calcutta University, where my uncle and grandfather studied law, but another link was to the beautiful small flat of Bhupen Hazarika on Golf Club Road, and I would experience a thrill every time I went there. His voice, deep-throated and nasal at the same time, became for me the voice of my native land. A legend in Assam and an icon in Calcutta, he became my role model for the multicultural identity that I too wanted. I can still hear his voice, shouting out for my father on a late Saturday evening in Fort William. "Colonel, where’s the whisky? I’m here!" he would say, standing arms akimbo on the porch below.

If I were to draw a visual montage of my native land and lay an audio track over it, it would be largely made up of my grandfathers’ homes in Guwahati along with corners of Calcutta, and Bhupen Hazarika singing about the great rivers of the east, the Brahmaputra and the Ganga, in Assamese and Bengali at the same time. The montage would have to end with the one track that he immortalised for millions, from the Paul Robeson original Ol’ Man River. When my father asked him to sing Ganga Bahti Ho Kyun twenty-five years ago at our house, I hadn’t heard Robeson’s original song about the Mississippi. When I did, it moved me to the core. Two voices, so different, and yet so much in love with the lands their rivers run through.

(Arnab Goswami is the editor-in-chief of Times Now.)